Imperial Delusions | by Fara Dabhoiwala | The New York Review of Books

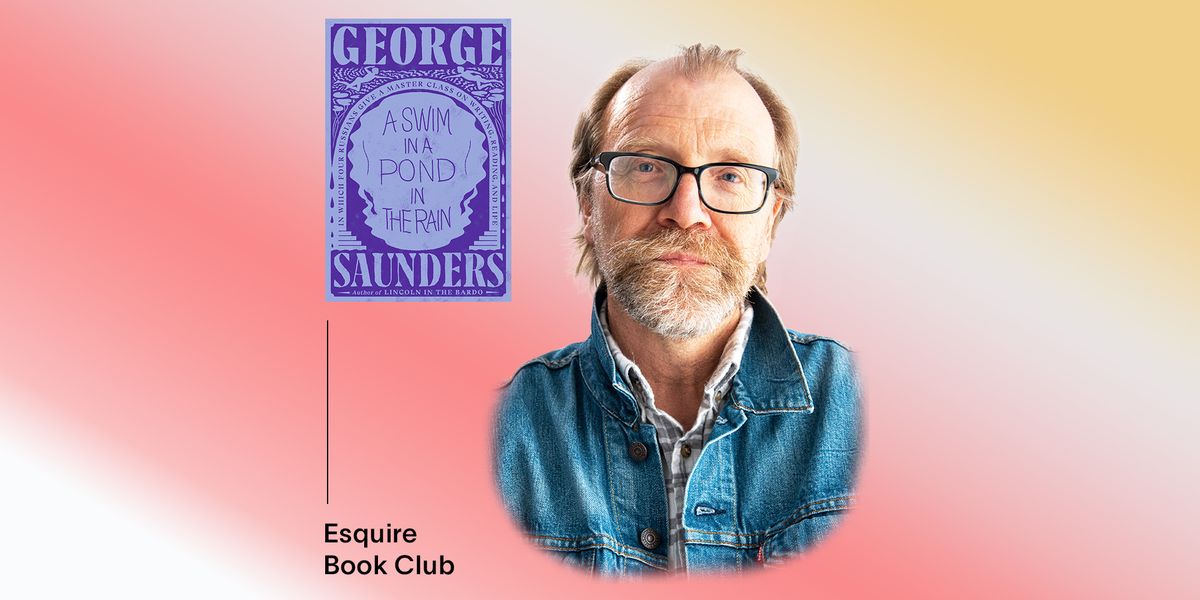

Time’s Monster: How History Makes History

Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities

Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

Winston Churchill, former prime minister of the United Kingdom, and Eric Williams, premier of Trinidad and Tobago, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, 1961

In the summer of 1932 Eric Williams arrived in England from the British colony of Trinidad. Like most of the island’s population, his family was so poor that he and his eleven siblings had rarely tasted milk. But from his earliest youth his father, a disillusioned postal clerk, obsessively pressured him to achieve academic success. There were no universities in the West Indies; few Trinidadians progressed beyond primary school, and almost all professions were reserved for whites. Yet Williams won a coveted government scholarship that enabled him to continue studying beyond the age of eleven, then an even rarer bursary to complete his secondary schooling, and finally, after three years of trying, one of the island’s two annual scholarships to a British university. He sailed for Oxford to take an undergraduate degree in history.

The white Englishman in charge of Trinidad’s Board of Education recommended him to one of the university’s colleges, the rich, ancient centers of its intellectual and social life. “Mr Williams,” he wrote, “is not of European descent, but is a coloured boy, though not black.” This did not help. He entered Oxford as a member of St. Catherine’s Society, the decidedly déclassé association for students who could not afford the high costs of a college. From then on, Williams flourished. He read insatiably, graduated at the top of his class, and entered the competition for a fellowship of All Souls College, Oxford’s greatest prize. He also embarked on research for a doctoral thesis about the ending of British slavery in the West Indies. This was a deeply unfashionable subject. Even in Trinidad, Williams had only ever been taught about the European past. A handful of Oxford’s faculty studied colonial history; the rest regarded it, he observed, with “general contempt.”

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/DFJYDZQLEJJF3F66K4NZMK4CCQ.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25419483/247092_Student_activist_doxxing_AKrales_1438.jpg)