Human intelligence can safeguard against artificial intelligence: individual differences in the discernment of human from AI texts

Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 25989 (2024 ) Cite this article

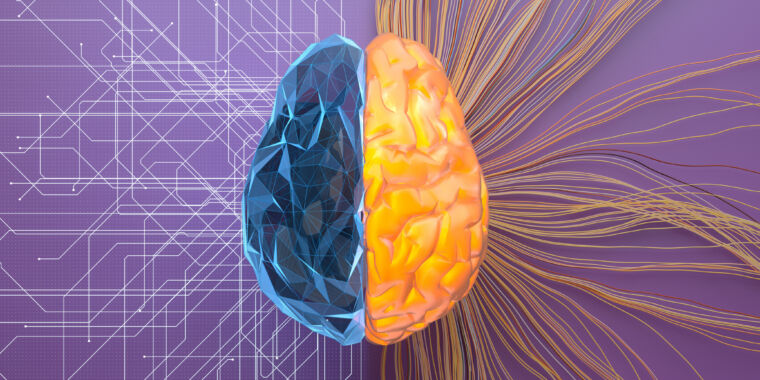

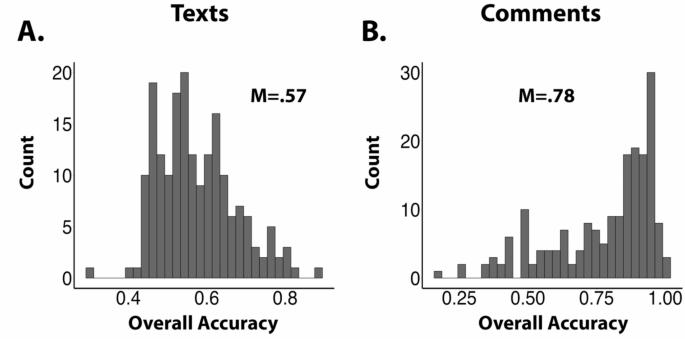

Artificial intelligence (AI) models can produce output that closely mimics human-generated content. We examined individual differences in the human ability to differentiate human- from AI-generated texts, exploring relationships with fluid intelligence, executive functioning, empathy, and digital habits. Overall, participants exhibited better than chance text discrimination, with substantial variation across individuals. Fluid intelligence strongly predicted differences in the ability to distinguish human from AI, but executive functioning and empathy did not. Meanwhile, heavier smartphone and social media use predicted misattribution of AI content (mistaking it for human). Determinations about the origin of encountered content also affected sharing preferences, with those who were better able to distinguish human from AI indicating a lower likelihood of sharing AI content online. Word-level differences in linguistic composition of the texts did not meaningfully influence participants’ judgements. These findings inform our understanding of how individual difference factors may shape the course of human interactions with AI-generated information.

Anticipating the rapid advance of modern computing, Alan Turing famously proposed a test to assess a machine’s “intelligence” by determining whether its textual outputs could trick a human evaluator into thinking that it was in fact a fellow human1. Technological developments in the decades that have followed underscore the prescience of his early thinking on the topic, with the latest crop of generative artificial intelligence (hereafter, gAI) models aggressively blurring the lines between human and artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities. The widening use, and ongoing enhancement of gAI systems, most especially large language models (e.g., ChatGPT2, Gemini3), has raised concerns about the potential for these tools to amplify cheating and deceitful self-presentation4,5,6,7,8, replace the human workforce9, and propagate disinformation10,11. In the scientific arena, AI-generated science abstracts are difficult to spot, and fears are growing that even whole-cloth studies fabricated with gAI could evade detection by the peer-review process12,13,14,15. Given these concerns, and the already wide proliferation of information originating from gAIs, it’s vital for us to better understand how human evaluators may engage with such material, and to clarify the conditions and psychological factors that predict when human evaluators may succeed, or fail, to make correct attributions regarding the origins (human or machine) of encountered content.