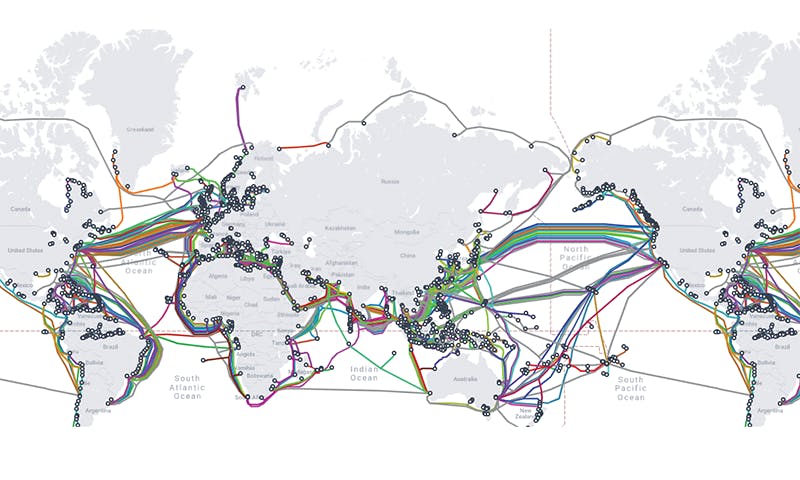

Your Data’s Strange Undersea Voyage

I n late December of 2021, the seafloor near the tiny South Pacific Island nation of Tonga began to rumble. The restive Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano was waking up. In the wee hours of January 15, after days of tremors, the bottom of the ocean finally cracked, disgorging the largest explosion on record. Four blasts of molten rock that packed 1 billion tons of force each sent a plume 36 miles into the sky. The blast was so powerful it could be heard in Alaska, 6,000 miles away. For days afterward, lashed by tsunamis and clouded beneath volcanic ash, the Tongans were unable to call for help.

Severed in the eruption was the single undersea telecommunications cable that could carry Tongan voices and emails the 514 miles to Fiji, and from there, to the rest of the world. It was as if a drunken god had tripped over the power cable to the collective computer. Screens went dark, phones went silent, and the internet disappeared. The Tongans were all alone.

“We were totally blank from the internet world for at least three days,” said Samisi Panuve, head of Tonga Cable, the company that owns the nation’s subsea connection. In fact, Panuve said, it would take weeks of exacting repair work at sea aboard highly specialized ships for the line to be fully restored.