Tiny fossil suggests spiders and their relatives originated in the sea

A new analysis of an exquisitely preserved fossil that lived half a billion years ago suggests that arachnids – spiders and their close kin – evolved in the ocean, challenging the widely held belief that their diversification happened only after their common ancestor had conquered the land.

Spiders and scorpions have existed for some 400 million years, with little change. Along with closely related arthropods grouped together as arachnids, they have dominated the Earth as the most successful group of arthropodan predators. Based on their fossil record, arachnids appeared to have lived and diversified exclusively on land.

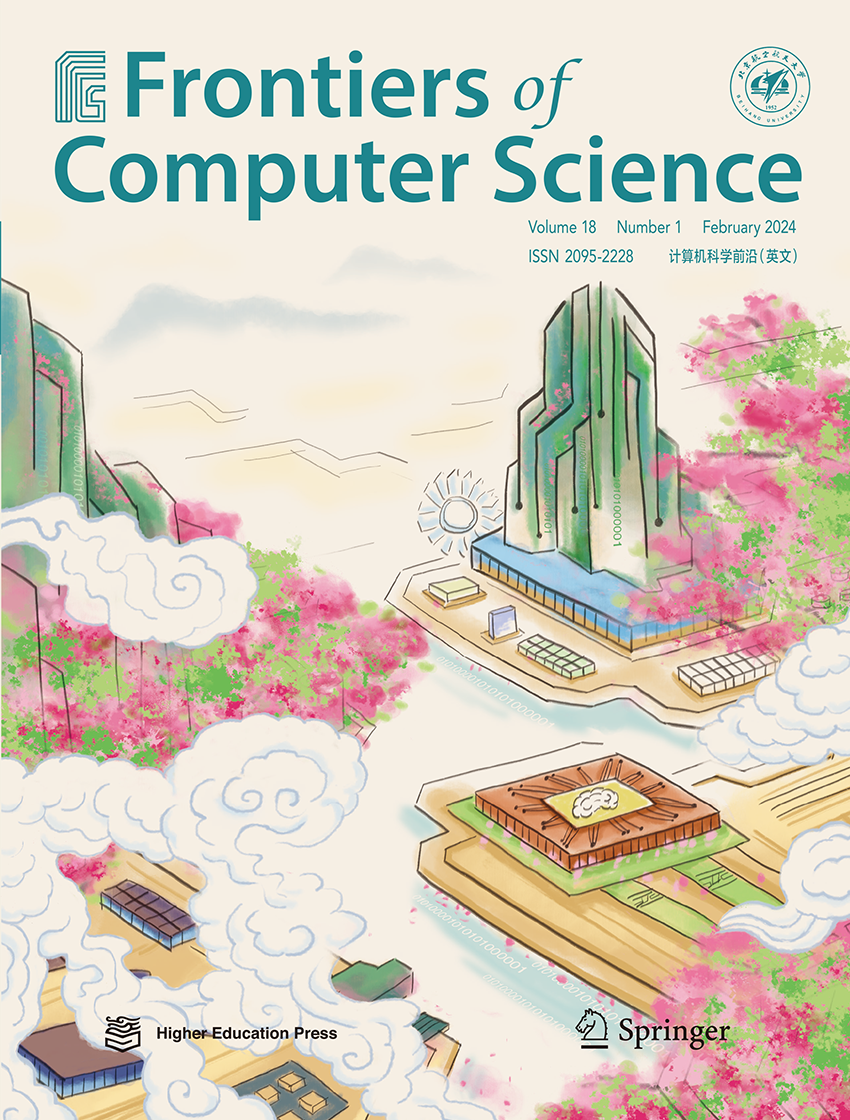

A side-by-side comparison of the brains of a horseshoe crab (left), the Mollisonia fossil (center) and a modern spider (right) reveal the surprising findings of this study: The organization of Mollisonia's three brain regions (green, magenta and blue) are inverted when compared to the horseshoe crab, and instead resemble the arrangement found in modern spiders.

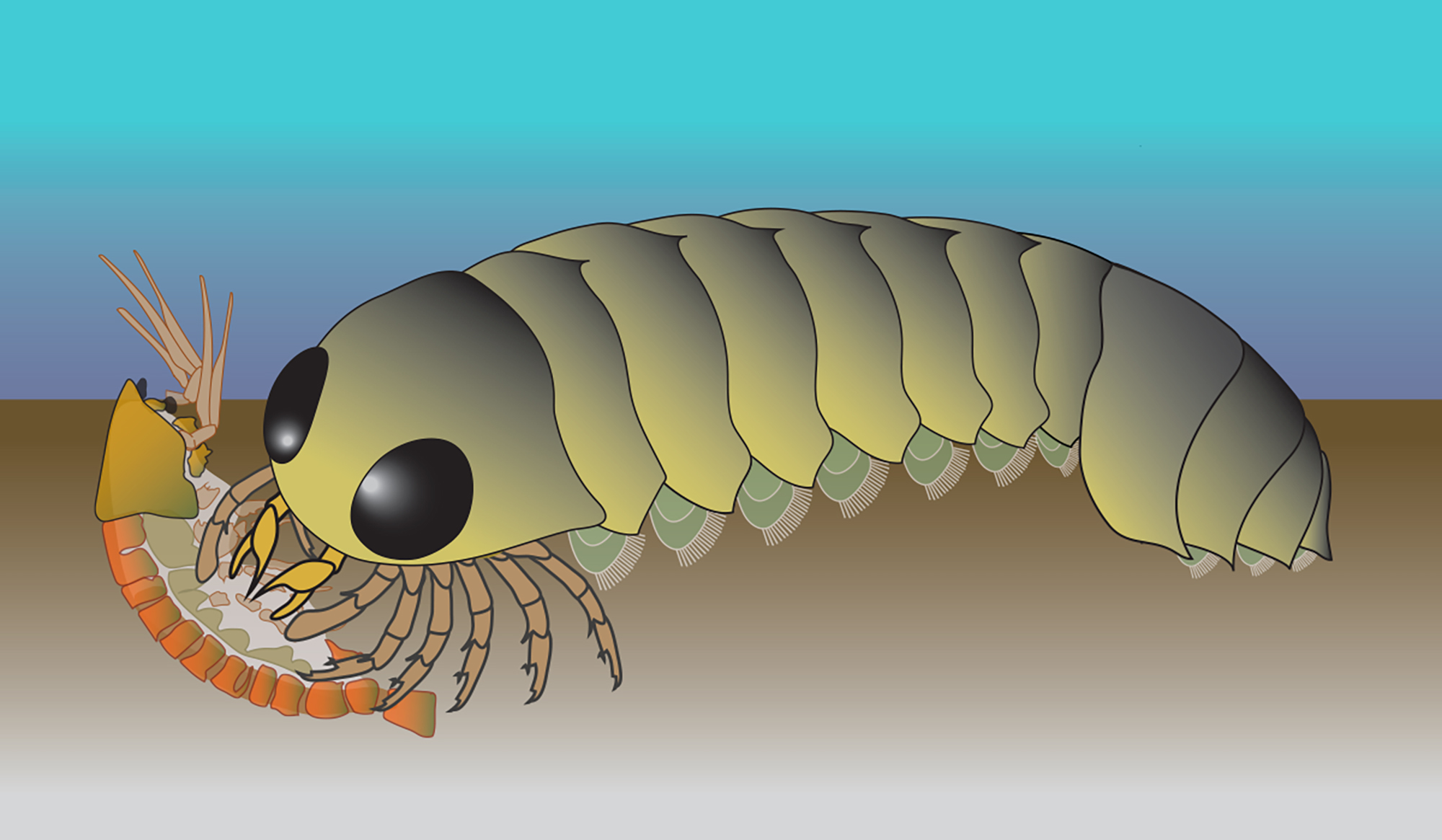

In a study led by Nicholas Strausfeld at the University of Arizona and published in Current Biology , researchers from the U.S. and United Kingdom undertook a detailed analysis of the fossilized features of the brain and central nervous system of an extinct animal called Mollisonia symmetrica. Until now, it was thought to represent an ancestral member of a specific group of arthropods known as chelicerates, which lived during the Cambrian (between 540 and 485 million years ago) and included ancestors of today’s horseshoe crabs. To their surprise, the researchers found that the neural arrangements in Mollisonia's fossilized brain are not organized like those in horseshoe crabs, as could be expected, but instead are organized the same way as they are in modern spiders and their relatives.