Are continuous glucose monitors a waste of time for people without diabetes?

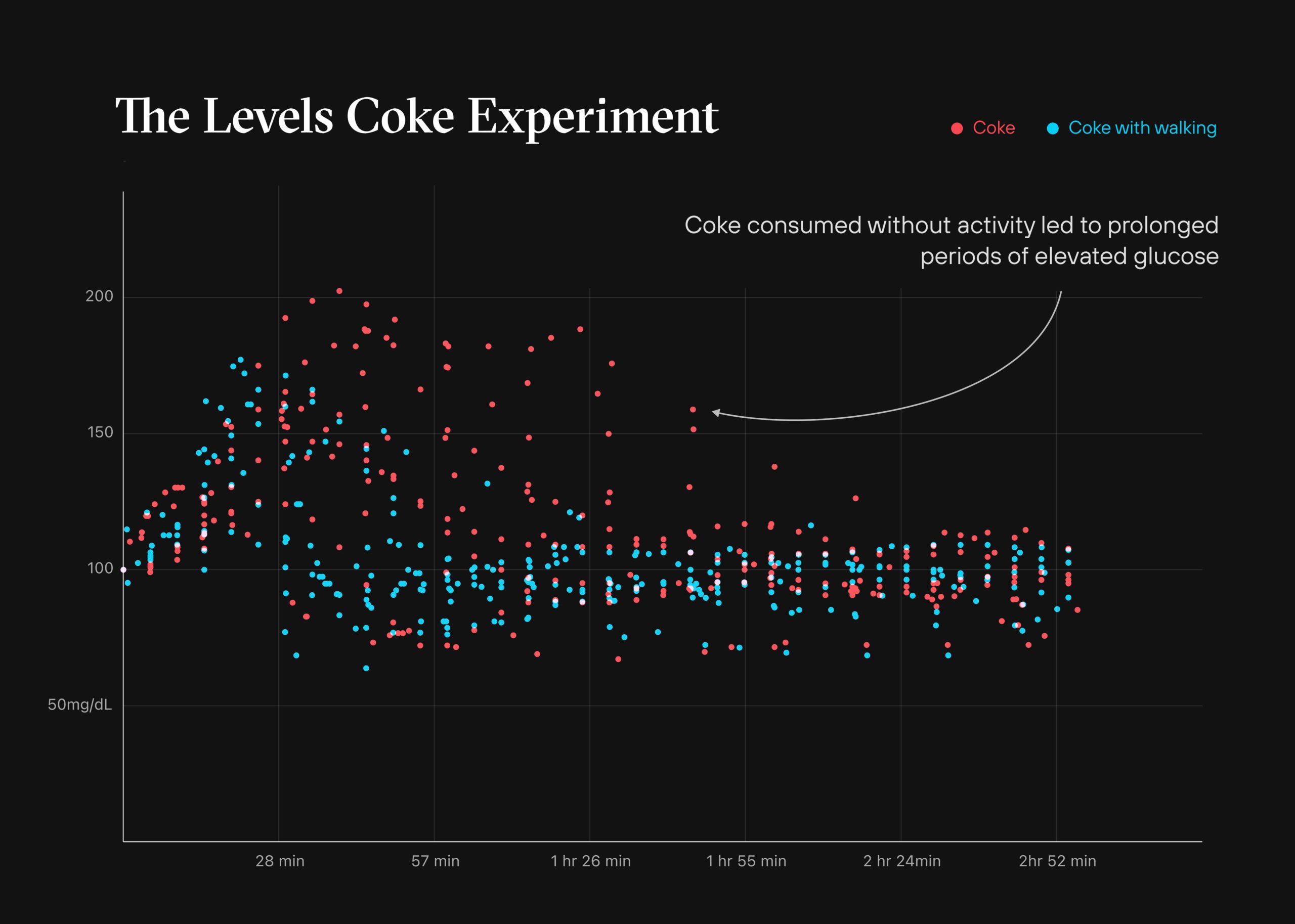

As some of you may already know, I’m a proponent of continuous glucose monitors, or CGMs, in my patients, even if they don’t have diabetes. Recently, a perspective in JAMA was published on this topic, highlighting the increasing number of start-up companies promoting the use of CGM in nondiabetics, and included some arguments suggesting that CGMs are “a waste of time and money” for this population. The author states that “… aside from anecdotal stories, there’s little evidence that people with normal glucose responses benefit from tracking their blood glucose,” according to the perspective. They also argue that because glucose fluctuations are so small in nondiabetics, a CGM doesn’t provide any meaningful information for them. I want to tell you why I not only disagree with these assertions, but also why this type of thinking may be dangerous to the health of hundreds of millions of Americans. First, arguing that there’s little evidence that people with normal glucose responses benefit from tracking their blood glucose is putting the cart before the horse. How do you know if someone has normal glucose responses without tracking their glucose first? Using CGM on someone with “normal” glucose as defined by standard measures such as fasting glucose or HbA1c can determine whether they truly do have tight glucose control and how they respond to different challenges, dietary or otherwise. Just because someone’s fasting glucose or HbA1c levels are considered normal doesn’t rule out the possibility that they have high glucose variability, which are large oscillations in blood glucose throughout the day, including episodes of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Fasting glucose and HbA1c levels don’t necessarily tell us if people are experiencing normal glucose responses. The only way to know if they are is to track their blood glucose. Is it safe to assume normal fasting glucose (i.e., less than 100 mg/dL) and normal HbA1c (i.e., less than 5.7%) tightly map to low variability and spikes in glucose? In our practice the answer is, how shall I say it, not even close. Over the past three years we have been tracking these metrics closely and found that at least one-third of the time HbA1c is an inaccurate predictor of average blood glucose relative to true average measured by CGM (and this discordance occurs in both directions, meaning sometimes HbA1c overestimates and sometimes it underestimates). Furthermore, we’ve seen how irrelevant morning fasting glucose can be as a predictor of in-depth glucose kinetics, outside of the extremes seen in patients with type 2 diabetes. In other words, in non-diabetics, a fasting morning blood glucose level of 90 vs 95 vs 100 vs 105 mg/dL can have much more to do with the previous night’s dinner, the quality of sleep that evening, or even the speed and suddenness with which they woke up that morning (and the concomitant cortisol surge) than their true health. In 2018, a study in nearly 60 participants found many individuals considered nondiabetic by standard measures showed high glucose variability determined by CGM. Severe glucose variability was present in one-quarter of normoglycemic individuals, with glucose levels reaching prediabetic ranges — defined as values greater than 140 mg/dL — up to 15% of the duration of CGM recordings, suggesting glucose dysregulation is more prevalent than we might think. But the recent JAMA perspective pointed to a 2019 study that was attempting to create reference ranges for glycemic profiles in more than 150 healthy nondiabetics that found they spent 96% of the time between 70 and 140 mg/dL based on about one week of CGM data, on average. This study was used to support the argument that there is in fact tight glucose control in these individuals, confirming that “normal is normal is normal,” as one of the study’s coauthors put it. A closer look at the findings, however, suggests otherwise. Median time spent with glucose levels above 140 mg/dL was 30 minutes a day and median time spent with glucose levels below 70 mg/dL was 15 minutes a day. Almost one-third of the participants had at least one hypoglycemic event, defined as a glucose level below 54 mg/dL, and almost half had at least one hyperglycemic event, defined as a glucose level above 180 mg/dL. Spending 30 minutes a day with glucose levels above 140 mg/dL may be the benchmark in this population, but that does not mean it’s optimal. The target I want my patients to hit in terms of the number of total glucose excursions above 140 mg/dL per week is zero. We never want to see glucose above 140 mg/dL. While the study didn’t report the number of weekly excursions, it’s probably safe to assume, given the averages, that I believe there’s plenty of room for improvement in the vast majority of the participants. One of the important lessons I’ve learned from consuming a lot of the scientific literature is that being skeptical of the interpretation of the results is the default position. (In that vein, my hope is that you are now skeptical of my interpretation at this point.) As I recently discussed in an AMA on the topic, higher glucose variability and higher (and more) peak glucose levels are each independently associated with accelerated onset of disease and death, even in nondiabetics. Prospective studies show that higher glucose variability in nondiabetics is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, frailty, cardiovascular death, cancer death, and death from any cause compared to lower glucose variability. Other prospective studies show similar trends for higher compared to lower peak glucose levels and several human experiments demonstrate that high glucose peaks induce endothelial dysfunction in healthy nondiabetic individuals, and higher postprandial glucose levels are also associated with higher carotid intima-media thickness, suggesting higher glucose peaks may accelerate the development of atherosclerosis, even in those with normal glucose tolerance. There is also remarkably robust data from the Interventions Testing Program, the gold standard of testing compounds for life extension in mice, demonstrating that two different drugs with completely different mechanisms of action (acarbose and canagliflozin) which suppress postprandial glucose peaks and both extended median and 90th percentile lifespan independent of body weight and average glucose levels. Granted, what’s true in mice might not translate to humans and the aforementioned prospective studies are of the observational epidemiological nature where skepticism of the results and the interpretation are required. In my partial defense, there’s a good deal of skepticism and scrutiny on my part, and those of the analysts that work with me, that factor into determining whether the data is worth considering or not. But I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a quote out there attributed to Einstein that says confirmation bias is one of the most powerful forces in the universe. When it comes to observational epidemiology, there’s always a selective interpretation of the evidence. Glucose control lives on a spectrum, but it conventionally gets lumped into three distinct categories: normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes, and diabetes. For example, whether your HbA1c is 4.6% or 5.6%, both are considered “normal” because they both fall under the diagnostic threshold of 5.7%. Once it hits 5.7%, so long as it does not exceed 6.4%, now you’ve got impaired glucose tolerance, also referred to as prediabetes. Once you’ve eclipsed the latter, whether your HbA1c is 6.5% or 12.5% (or even higher), you’re categorized as having type 2 diabetes. In most cases of type 2 diabetes, an individual traverses from one bucket to the next as their HbA1c slowly climbs from normal to impaired to outright diabetic. This doesn’t happen overnight, but too often it’s only confronted when the diabetes or prediabetes threshold is reached at a snapshot in time. Progressing from an HbA1c of 4.6% to 5.6% represents estimated average glucose levels climbing from 85 to 114 mg/dL. This should be setting off alarm bells along the way, but I worry that those bells aren’t ringing because it’s not deemed necessary to keep a close eye on blood glucose in someone with normal glucose tolerance. I have a friend who flies helicopters. The other day she was telling me that there is a warning system in place for when minuscule fragments of metal are in the hydraulic fluid. Though they pose no immediate danger, if left in place long enough, they will erode gears and potentially lead to a catastrophic outcome. So you overhaul the hydraulics as soon as you get the warning, not when the gears start grinding. Viewing glucose regulation as abrupt categories like this rather than a spectrum is probably one of the biggest reasons why more than 120 million Americans have diabetes or prediabetes. In the vast majority of cases, today’s normal individual is tomorrow’s diabetic patient if something isn’t done to detect and prevent this slide. Not only that, but prospective studies also demonstrate a continuous increase in the associated risk for cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular death, and deaths from all causes throughout a broad range of HbA1c values beginning at 5.0%. Similar trends are observed for elevated HbA1c values and higher rates of frailty, cognitive decline and dementia, COVID-19 hospitalizations and death, and cancer mortality, suggesting that lowering your average glucose levels even when they might be deemed normal by traditional cutoff points can make a difference. To recap my position and interpretation of the data available (more of which you can find in the AMA 24 show notes), lower is better than higher when it comes to average glucose, glucose variability, and glucose peaks, even in nondiabetics. In other words, there’s a lot of evidence suggesting that people with glucose in the normal range can benefit from lowering their numbers. Let me give you an anecdote, among several I could share, to demonstrate why I find CGM useful in nondiabetics. I have a patient who came to me with normal glucose tolerance by standard metrics. He began CGM and after about two weeks it revealed an average glucose of 104 mg/dL over that time. The standard deviation in his glucose readings, which is a metric of glucose variability, was 17 mg/dL. He averaged more than five events per week in which his glucose levels exceeded 140 mg/dL. All three of these metrics are considered normal by conventional standards, but does that mean there’s no room for improvement? I like to see my patients with a mean glucose below 100 mg/dL, a glucose variability below 15 mg/dL, and, as noted above, no excursions of glucose above 140 mg/dL. After about a four-week intervention that included exercise changes and nutritional modifications his average glucose fell to 84 mg/dL, his glucose variability to 13 mg/dL, and he had zero events exceeding 140 mg/dL. If he can maintain this way of living in the long-run, it’s likely to translate into an improvement in healthspan and reduce his risk of glucose impairment. Going back to the first argument from the perspective, it may be true that aside from anecdotal accounts, there’s little evidence that people with normal glucose responses benefit from tracking their blood glucose, but don’t confuse an absence of evidence with evidence of absence. I can’t point you to a long-term randomized-controlled clinical trial rejecting the hypothesis that people with normal glucose responses don’t benefit from tracking their blood glucose because those trials don’t exist (yet, hopefully), but don’t confuse an absence of evidence with evidence of absence. There are examples where the randomized-controlled clinical trial data isn’t there, but we still have a strong reason to believe it’s true. While it’s not the same level of confidence I have in parachutes improving survival when jumping out of an airplane at 10,000 feet or smoking two packs of Marlboros a day increasing the risk of lung cancer, I do believe that relatively healthy people who track their glucose responses will fare better in the long run than those who don’t. An important question related to these kinds of trials, and one that I can’t explore without at least doubling the length of this article is: what kinds of behavioral changes move the needle and keep it there in the long run? In other words, the reason why I have confidence that tracking glucose responses if beneficial is because I have confidence that we can optimize them (and even more confidence that we can at least stave off their decline). If we don’t have any effective interventions, saying we don’t get any benefit from CGMs is like a group of carpenters saying they don’t get any benefit from tape measures. If that’s the case, maybe it’s time to reconsider our approach to the problem. Overall, there are some interesting points from the perspective, some of which I haven’t addressed here, but I disagree with the notion that the use of CGM is “a waste of time and money that diverts consumers’ attention from useful interventions,” or that it “it’s just like a supplement—we don’t know whether it works or not,” as some experts think. For many people (certainly for me and most of our patients), when you start wearing CGM, it’s 90% “insight” and 10% behavioral. After a few months, the situation flips. You now have a good idea of what triggers the spikes (i.e., less insight), but it becomes a remarkable—in fact, it’s hands-down the best I’ve seen yet—accountability tool (i.e., more behavioral). It’s simultaneously a behavioral and analytical tool that can track and uncover strategies and tactics which can actually save an enormous amount of time and money by preventing bad outcomes in the future. Instead of (or in addition to) questioning groundbreaking technology like CGM, we should do more questioning of ourselves and how we use it.