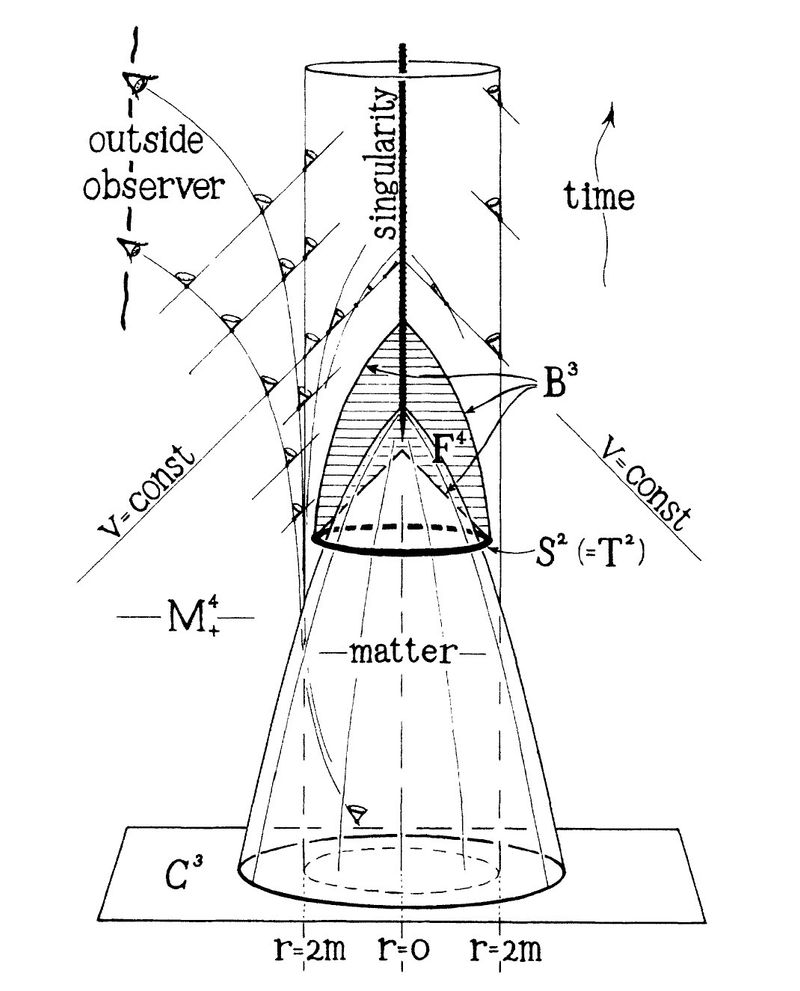

The Drawing That Earned Sir Roger Penrose a Nobel Prize

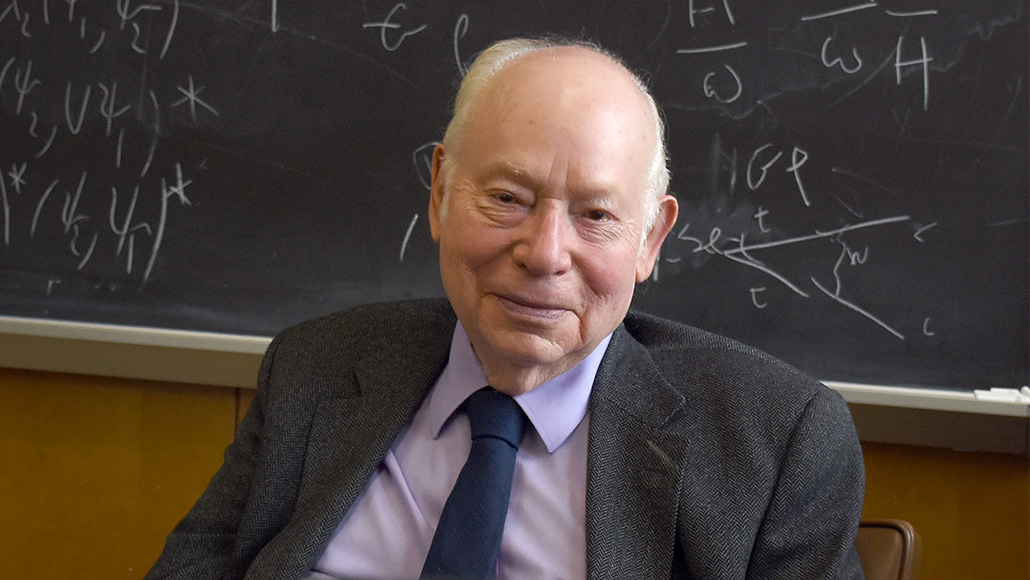

In 1965, in an inspired and disarmingly clear article – so brief that the text does not quite fill three journal pages – Roger Penrose draws a figure to summarize his ingenious mathematical proof that would earn him the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity.” The now legendary Penrose distilled his mathematical calculation into a single paragraph and then distilled the proof even further into a single image that can be read by the initiated. The powerful conclusion: black holes are an inevitable consequence of unhindered gravitational collapse.

The term “black hole” had not yet been coined, and wouldn’t be until the influential American relativist John Archibald Wheeler concluded a lecture in 1967 with the image, “[The star] like the Cheshire cat fades from view. One leaves behind only its grin, the other, only its gravitational attraction…light and particles go down the black hole…” Quasi-stellar radio sources were a newly observed mystery, so named since the signals appeared to come from a single location like a star. Some astronomers hypothesized that the emission originated in the formation of a supermassive black hole (using the moniker “black hole” anachronistically) millions or hundreds of millions times the mass of our Sun.

Although intriguing hypothetical candidates for unexplained sources, black holes were not assured to exist even theoretically. The descriptions of the spacetime structure around hypothetically collapsed stars leaned on extremely simplified symmetries for their construction, not to detract from the significant accomplishment the solutions represent. The first mathematical model of a black hole was presented to Einstein in a letter within six months of the publication of the General Theory of Relativity. The letter arrived from the Russian front during WWI from his friend Karl Schwarzschild, an astronomer and enlisted German soldier, and includes words of such bewildering optimism they are often quoted with some bemusement: "As you see, the war treated me kindly enough, in spite of the heavy gunfire, to allow me to get away from it all and take this walk in the land of your ideas." Schwarzschild imagined a perfect sphere with all the mass of a star crushed to a point. He didn’t ask how nature would create such a thing. He simply chose to imagine it. Nearly a half century later, in 1963, Roy Kerr discovered the mathematical solution for an idealized, perfect, spinning black hole. Despite these formal descriptions, the skepticism towards the existence of black holes in nature was reasonable. The mathematical models were clever but so idealized as to be impossible to achieve in reality.