Modern theories of human evolution foreshadowed by Darwin’s Descent of Man

Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man was published in 1871. Ever since, it has been the foundation stone of human evolutionary studies. Richerson et al. reviewed how modern studies of human biological and cultural evolution reflect the ideas in Darwin’s work. They emphasize how cooperation, social learning, and cumulative culture in the ancestors of modern humans were key to our evolution and were enhanced during the environmental upheavals of the Pleistocene. The evolutionary perspective has come to permeate not just human biology but also the social sciences, vindicating Darwin’s insights.

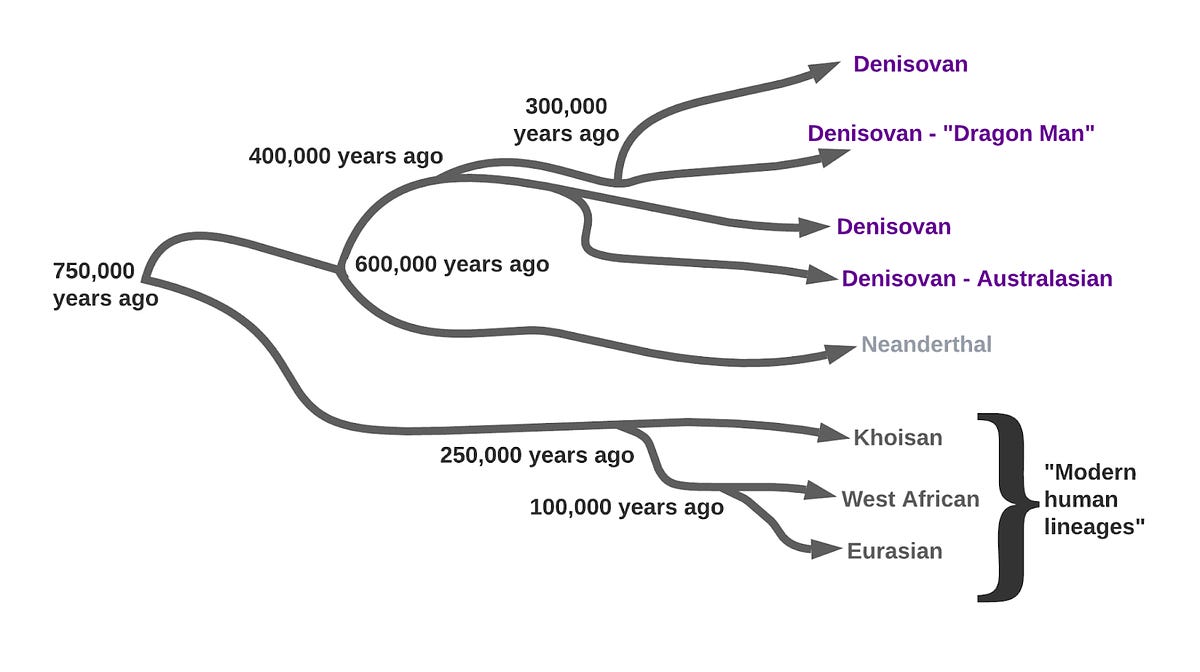

Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man, published on 24 February 1871, laid the grounds for scientific studies into human origins and evolution. We look at the advances in our understanding of these processes through the lenses of modern speciation theory. Applying this theory to specific cases requires one to identify and understand the nature of (i) the ancestor and various preexisting adaptations and traits that it possessed that allowed or simplified the speciation process, (ii) evolutionary forces responsible for major differences between the emergent species and its close relatives, and (iii) the most salient adaptations characteristic of the new species and its evolutionary history (such as genetic, morphological, behavioral, spatial, and temporal).

Modern research shows that we share many developmental, physiological, morphological, cognitive, and psychological characteristics as well as about 96% of our DNA with the anthropoid apes. We now know that since our last common ancestor with the other apes 6 million to 8 million years ago, human evolution followed the path common for other species with diversification into closely related species and some subsequent hybridization between them. Since Darwin, a long series of unbridgeable gaps have been proposed between humans and other animals. They focused on tool-making, cultural learning and imitation, empathy, prosociality and cooperation, planning and foresight, episodic memory, metacognition, and theory of mind. However, new insights from neurobiology, genetics, primatology, and behavioral biology only reinforce Darwin’s view that most differences between humans and higher animals are “of degree and not of kind.” What makes us different is that our ancestors evolved greatly enhanced abilities for (and reliance on) cooperation, social learning, and cumulative culture—traits emphasized already by Darwin. Cooperation allowed for environmental risk buffering, cost reduction, and the access to new resources and benefits through the “economy of scale.” Learning and cumulative culture allowed for the accumulation and rapid spread of beneficial innovations between individuals and groups. The enhanced abilities to learn from and cooperate with others became a universal tool, removing the need to evolve specific biological organs for specific environmental challenges. These human traits likely evolved as a response to increasing high-frequency climate changes on the millennial and submillennial scales during the Pleistocene. Once the abilities for cumulative culture and extended cooperation were in place, a suite of subsequent evolutionary changes became possible and likely unavoidable. In particular, human social systems evolved to support mothers through the recruitment of males and nonreproductive females. The most distinctive feature of our species, language, appeared arguably driven by selection for simplifying cooperation. Reliance on social learning and conformity led to the emergence of new factors constraining and driving human behavior, such as morality, social norms, and social institutions. These forces often act against the immediate biological or material interests of individuals, promoting instead the interests of the society as a whole or of its powerful segments. Continuous engagement in cooperation has led to the evolution of strong coalitionary psychology, which can bring us together whenever we perceive that our identity group faces outside threats. Coalitionary psychology also has an undesirable byproduct: often negative or even hostile reaction to others who differ from us in their looks, behaviors, beliefs, caste, or class.