What Happened When Hitler Took On Germany’s Central Banker

Adolf Hitler’s first week s as chancellor were filled with so many excesses and outrages—crushing states’ rights, curtailing civil liberties, intimidating opponents, rewriting election laws, raising tariffs—that it was easy to overlook one of his prime targets: the German central bank.

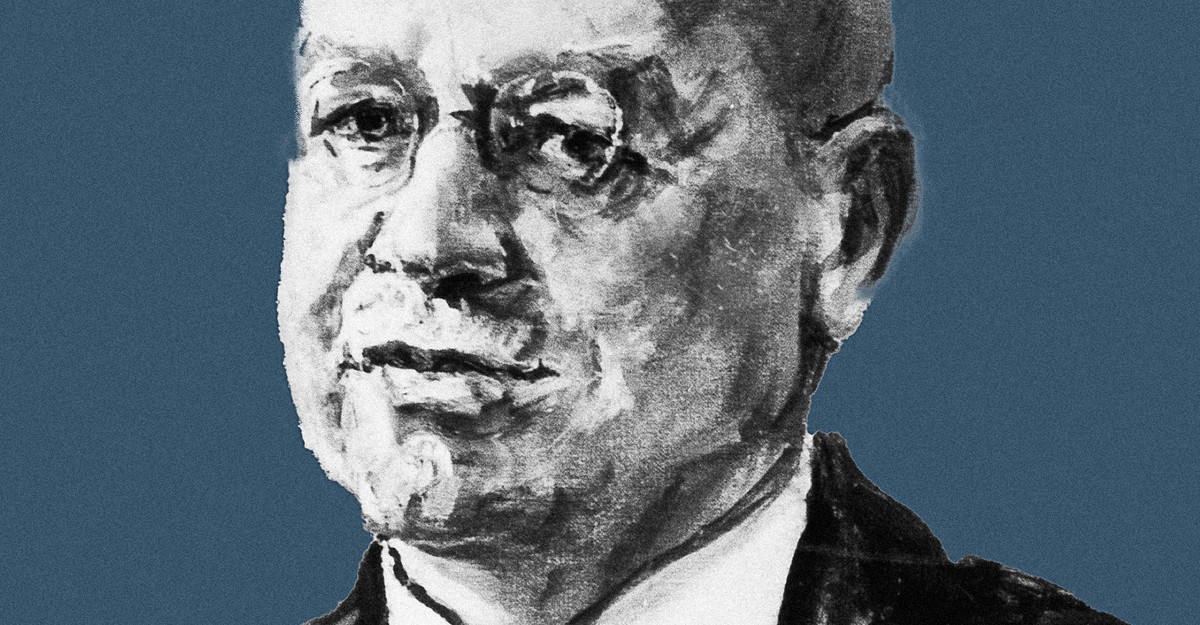

The Reichsbank president was a man named Hans Luther, a fiscal conservative who subscribed to the “golden rule” of banking, which stipulated that a country’s indebtedness should never exceed its obligations. In his adherence to protocol and policy, Luther could be “holier than the Pope,” according to Lutz Schwerin von Krosigk, who served as the German finance minister from 1932 to 1945.

On the afternoon of Monday, January 30, 1933, just hours after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Luther stood in Hitler’s office with a complaint. Nazi storm troopers, known as the SA, had forced their way into the Reichsbank building in central Berlin, despite what Luther described as “emphatic protests” by bank personnel, and hoisted a swastika flag over the bank.

“I pointed out to Hitler that the SA actions were against the law,” Luther recalled, “to which Hitler immediately answered that this was a revolution.” Luther informed Hitler in no uncertain terms that the Reichsbank was not part of his revolution. It was an independent fiscal entity with an international board of directors. If any flag were to be flying over the bank, it would be the national colors, not the banner of his political party. The next morning, the swastika flag was gone.