What are you Haydn? The hoaxers who fooled the classical music world

One wrote six sonatas and claimed they were by Haydn. Another used a ghostwriter to write his symphony – and pretended to be deaf. So how did they manage to hoodwink the experts?

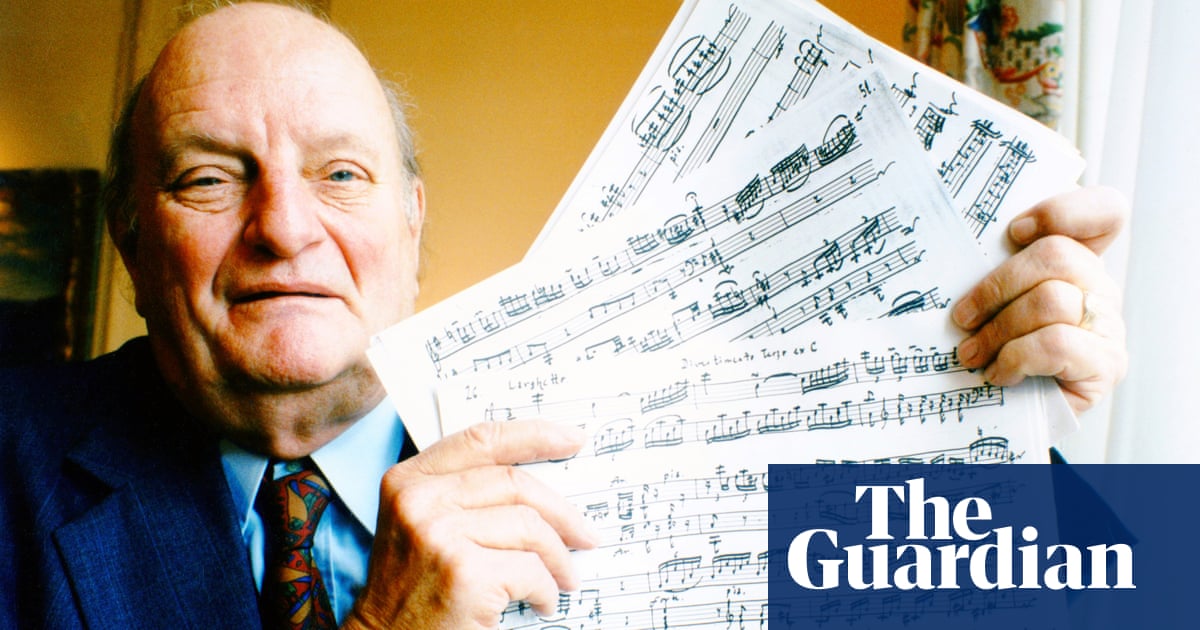

I n 1993, completely out of the blue, the Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda was sent a photocopy of a manuscript purporting to be six lost Haydn keyboard sonatas. It came with a letter from a little-known flautist from Münster, Germany called Winfried Michel, who told Badura-Skoda that he’d been given it by an elderly lady whose identity he could not reveal.

Badura-Skoda was suspicious, but once he played the music, he became sure that the works were real. He asked his wife Eva, a musicologist, to examine the manuscript. Although the music wasn’t in Haydn’s hand, she believed it to be an authentic copyist’s score dating from around 1805 and originating in Italy. They checked with the Haydn scholar, HC Robbins Landon, and he too was convinced. He penned an article for BBC Music Magazine, headlined Haydn Scoop of the Century, tipped off the Times, and called a press conference for 14 December 1993.

Within hours, the Joseph Haydn Institute in Cologne declared the manuscript to be a fake. An expert from Sotheby’s in London agreed. The Badura-Skodas had been hoaxed, or so it seemed. The following February, Eva gave a talk in California titled: The Haydn Sonatas: A Clever Forgery. Paul played a selection of the works – in a confused state of mind. Eva told the music scholar Michael Beckerman, reporting for the New York Times, “My husband still thinks they’re genuine,” raising difficult questions about truth and art. What did Paul believe he was playing? What was the audience hearing? And did it matter?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25803712/HoneyCouponsTrio_LQ.jpg)