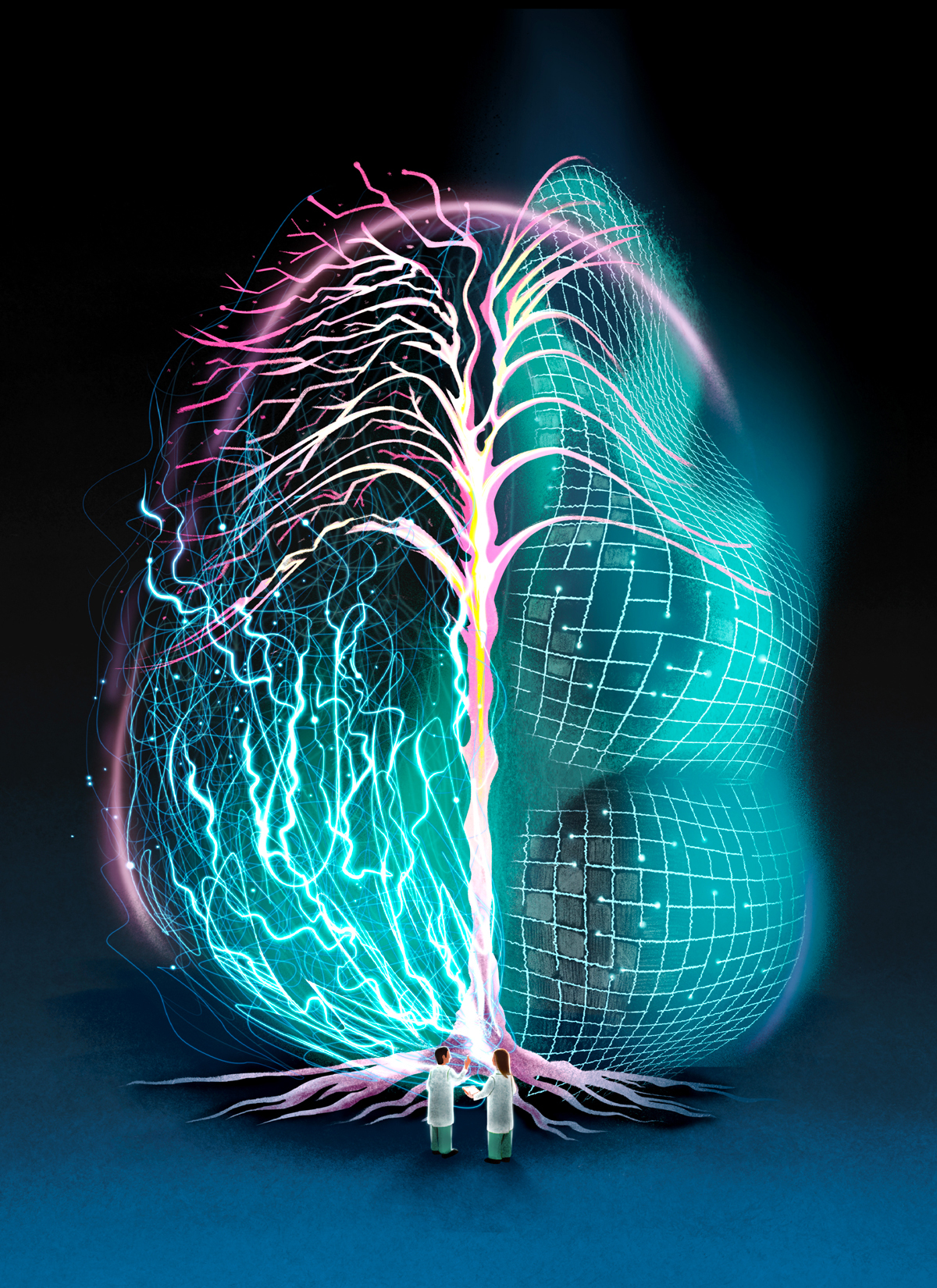

Hibernation allows many animals to time-travel from difficult times to plenty. Could humans learn how to do it too?

is professor of sleep physiology and tutorial fellow in medicine at the University of Oxford, as well as vice-president of the European Sleep Research Society and a TEDx speaker.

The conventional view is that humans and other creatures around us live between periods of waking and sleeping. But it is not true. Many have mastered the art of hibernating, which allows them to spend quite a lot of their life in a mysterious state of suspended animation – sometimes more than half of it. What is hibernation, and is it something that humans might be capable of?

At the dawn of scientific enquiry into hibernation (from the Latin hibernus, pertaining to winter) in the mid-19th century, it was defined by Peter A Browne in an 1847 tract as ‘a natural, temporary, intermediate state, between life and death; into which some animals sink, owing to an excess of heat, or of cold, or of drought, or want of oxygen’. That’s a good first approximation. Now we know that – from dormice and bears, to hedgehogs, ground squirrels, bats and even tropical primates – hibernation is a very common phenomenon, found among representatives of at least seven different orders of mammals. It appears in many forms, which makes it difficult to define unequivocally, let alone imagine what it might look like in humans. As another early study points out: ‘we do not find that any two animals, however closely allied, hibernate in precisely the same manner, nor do individuals of the same species always hibernate alike’.

Nevertheless, there is a cluster of features typical of hibernation. The most parsimonious description would include reference to a controlled reduction in metabolism, reflected in a slowing down of many physiological and biochemical processes in the body. In sci-fi movies, hibernating humans are often depicted lying in pods, completely immobile and seemingly unconscious, and it is implied that their body temperature is very low – hence it is often called ‘cryosleep’ or something similar. Any mention of how exactly human hibernation is achieved in those conditions, or what triggers ‘awakenings’ from hibernation, is conveniently avoided, as if that were a trivial matter not deserving attention.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25745281/nasa_blue_origin_lander.png)