The leak that brought the H-bomb debate out of the cold | Restricted Data

In September 1949, the United States unambiguously detected radioactive residues which indicated that the Soviet Union had, some weeks before, detonated their first atomic bomb. President Truman was initially inclined to keep the discovery secret, to avoid panic among Americans and their foreign allies, but was convinced by his advisors, including an impassioned David Lilienthal, head of the Atomic Energy Commission, that this was folly. The Soviets, they argued, would likely be announcing it soon anyways, and it would look better for the US to show that it was on top of things and unruffled by these developments. Truman finally agreed, and released a short statement indicating that an “atomic explosion” had taken place in the USSR (he was deliberately coy on whether it was a bomb or not), and indicating that this was entirely in accord with expert predictions about Soviet capabilities (not entirely true, but not entirely false).1

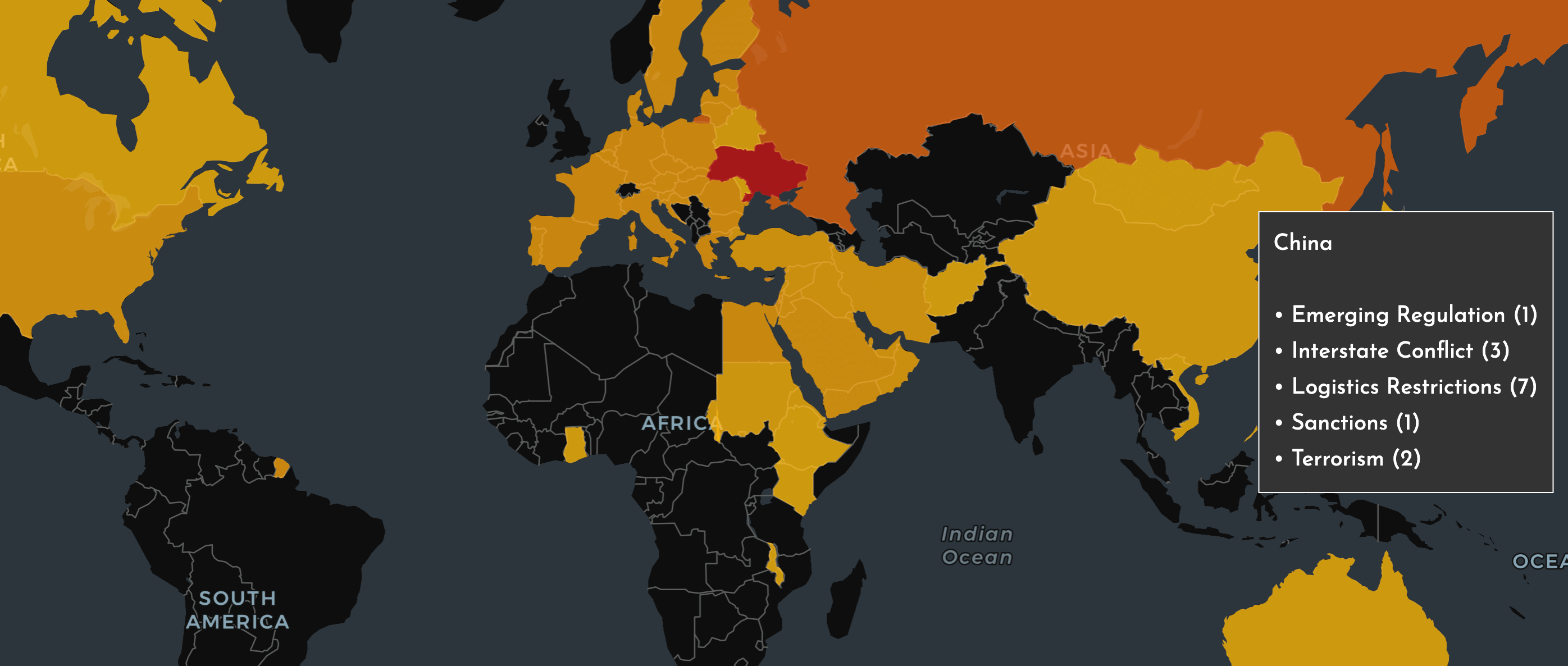

What should the US response be to the loss of its nuclear monopoly? This question raged in the weeks afterwards. One of the proposals, led by Edward Teller and championed by AEC Commissioner Lewis Strauss, was to push for an even bigger weapon: the “Super,” or hydrogen bomb. The Super would dwarf fission weapons, it was believed, and show the American people, America’s foreign allies, and America’s foreign enemies who exactly was in charge. As momentum grew behind this still-secret push for a “crash” H-bomb program, opposition emerged. J. Robert Oppenheimer and the AEC’s General Advisory Committee would, in late October 1949, issue a scathing report that condemned the idea on technical, policy, and moral grounds. Not only would a crash program divert vital resources from the US fission weapons program at a crucial time (and they not only did not know how to make an H-bomb in 1949, they didn’t even know for sure that it could be built), but a world with H-bombs would ultimately be more dangerous for the United States than the Soviets (because the US keeps so much of its people and wealth in large, concentrated cities on the vulnerable coasts), but a weapon in the megaton range was potentially a weapon of “genocide” (their wording), and thus not compatible with American values.2

.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25012282/236834_Ray_Ban_Meta_Smart_Glasses_AKrales_0608.jpg)