Facts Will not Save You - by Seva Gunitsky - Hegemon

A few days ago Microsoft published a list of the 40 jobs most likely to be replaced by AI. The first two entries are translators and historians, which made me laugh. The two jobs have one thing in common — they are acts of interpretation that are never recognized as such by outsiders. It’s probably self-evident in the tech world that history is a matter of assembling facts. A kind of mechanical curation, like sweeping loose pebbles into neat piles. This delusion reflects a larger hubris— the belief that facts can be wrenched from their social context and be made shinier, more objective in the process.

But as Goethe said, every fact is already a theory. That’s why facts cannot save you. “Data” will not save you. There can be no objective story since the very act of assembling facts requires implicit beliefs about what should be emphasized and what should be left out. History is therefore a constant act of reinterpretation and triangulation, which is something that LLMs, as linguistic averaging machines, simply cannot do. E.H. Carr wrote about this sixty years ago: “The belief in a hard core of historical facts existing objectively and independently of the interpretation of the historian is a preposterous fallacy, but one which it is very hard to eradicate.” The facts never speak for themselves; the historian always speaks for them.

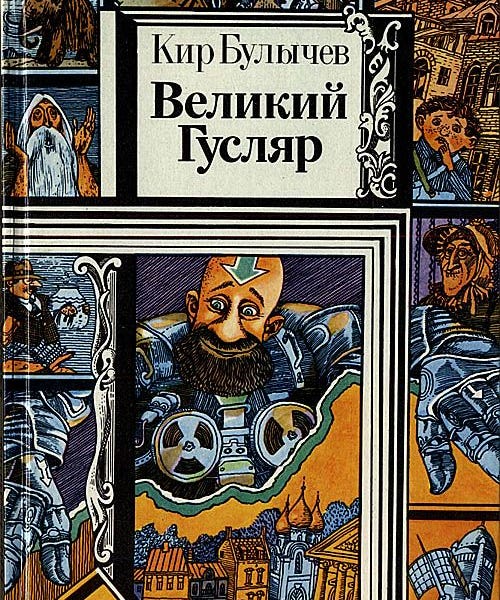

The translator’s case is less obvious. We already use AI to translate reams of text, often with passable results. We’ve grown used to consuming imperfect language when the stakes are low: a twitter post, a menu, a news article. But the suggestion that translation as a craft can be replaced with AI is a category error, for the same reasons as above. Translation is not an act of mechanically swapping words between languages. It’s an act of cultural mediation, especially with fiction. A translator has to know not just what the author wrote but what the author meant, and how that meaning will be received by an audience with a very different set of assumptions, idioms, and taboos.