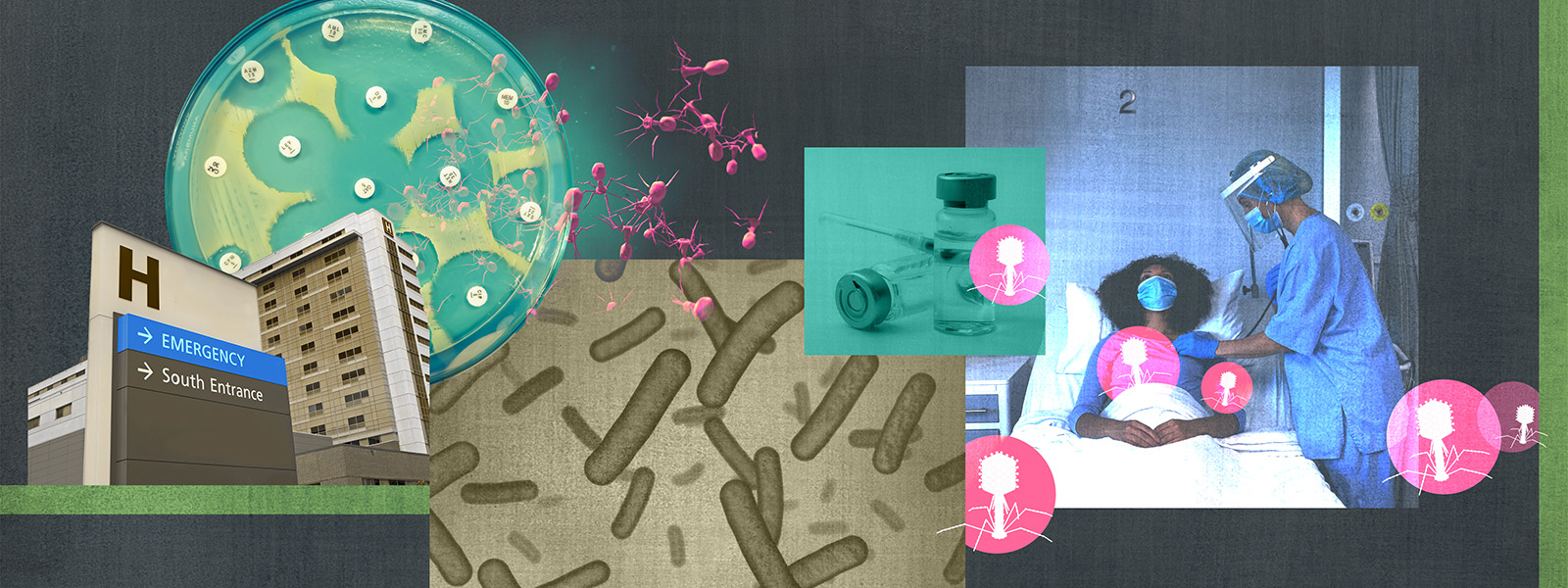

What if a virus could reverse antibiotic resistance?

Antibiotic resistance is a serious problem, especially in hospitals. Could an old, disused therapy involving viruses offer a way to counter it?

In promising experiments, phage therapy forces bacteria into a no-win dilemma that lowers their defenses against drugs they’d evolved to withstand

Peering through his microscope in 1910, Franco-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Hérelle noticed some “clear spots” in his bacterial cultures, an anomaly that turned out to be viruses preying on the bacteria. Years later, d'Hérelle would come to use these viruses, which he called bacteriophages, to treat patients plagued with dysentery after World War I.

In the decades that followed, d'Hérelle and others used this phage therapy to treat bubonic plague and other bacterial infections until the technique fell into disuse after the widespread adoption of antibiotics in the 1940s.

But now, with bacteria evolving resistance to more and more antibiotics, phage therapy is drawing a second look from researchers — sometimes with a novel twist. Instead of simply using the phages to kill bacteria directly, the new strategy aims to catch the bacteria in an evolutionary dilemma — one in which they cannot evade phages and antibiotics simultaneously.

Leave a Comment

Related Posts

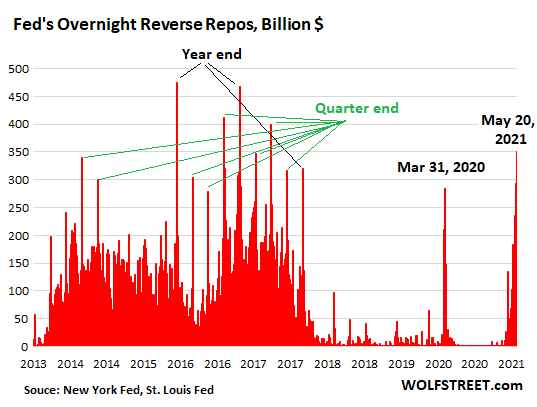

Fed Drains $351 Billion in Liquidity from Market via Reverse Repos, as Banking System Creaks under Mountain of Reserves

Comment

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25831586/STKB310_REDNOTE_XIAOHONGSHU_B.jpg)