In Praise of Print: Why Reading Remains Essential in an Era of Epistemological Collapse

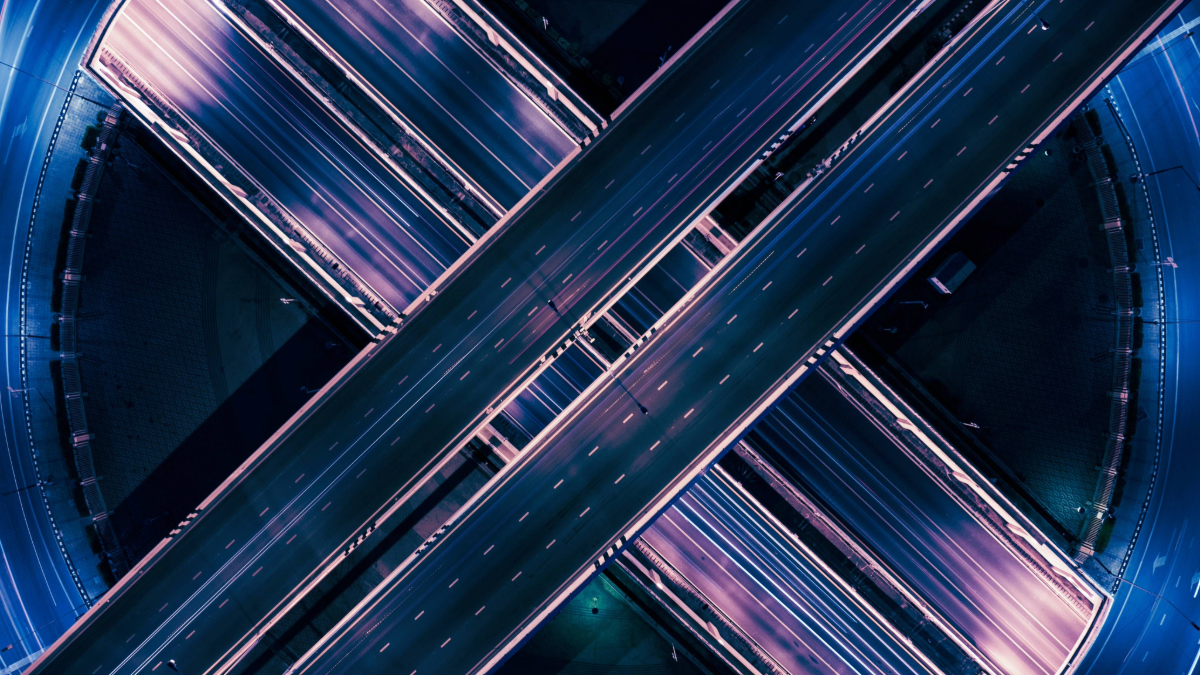

When the witty and wry English fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett interviewed Bill Gates for GQ in 1995, only 39% of Americans had access to a home computer. According to the Pew Research Center, the number who were connected to the internet was a paltry 14%. At the dawn of the internet age, when optimistic bromides about the information superhighway to the 21st century were replete in politics and culture, the author of the “Discworld” series was less sanguine.

While talking to the CEO of Microsoft, Pratchett asked what would happen if a writer disseminated on the internet something atrocious and libelous, say a pseudo-academic work of Holocaust denial. “There’s a kind of parity of esteem of information on the net,” said Pratchett, “there’s no way of finding out whether this stuff has any bottom to it or whether someone has just made it up.” Predictably, Gates denied the threat of any sort of epistemological collapse. Without offering any mechanism for doing so, the billionaire told the author that “you will have authorities on the net… The whole way that you can check somebody’s reputation will be so much more sophisticated.” Google was three years into the future—Facebook would be founded in nine years—Twitter in eleven. If Pratchett seemed sardonic and cynical in 1995, then Gates’ pollyannish, Panglossian exuberance appears positively psychotic three decades later.

Pratchett’s warning may have been lonely during that distant age of unbridled tech-enthusiasm, but he wasn’t the only Cassandra warning about reality through a smartphone screen darkly. Astrophysicist Carl Sagan predicted in his 1995 The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark that “when awesome technological powers are in the hands of the very few… [and] when the people have lost their ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority” the nation would “slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness.”

.jpg?mode=max)