'Universal' cancer vaccine heading to human trials could be useful for 'all forms of cancer'

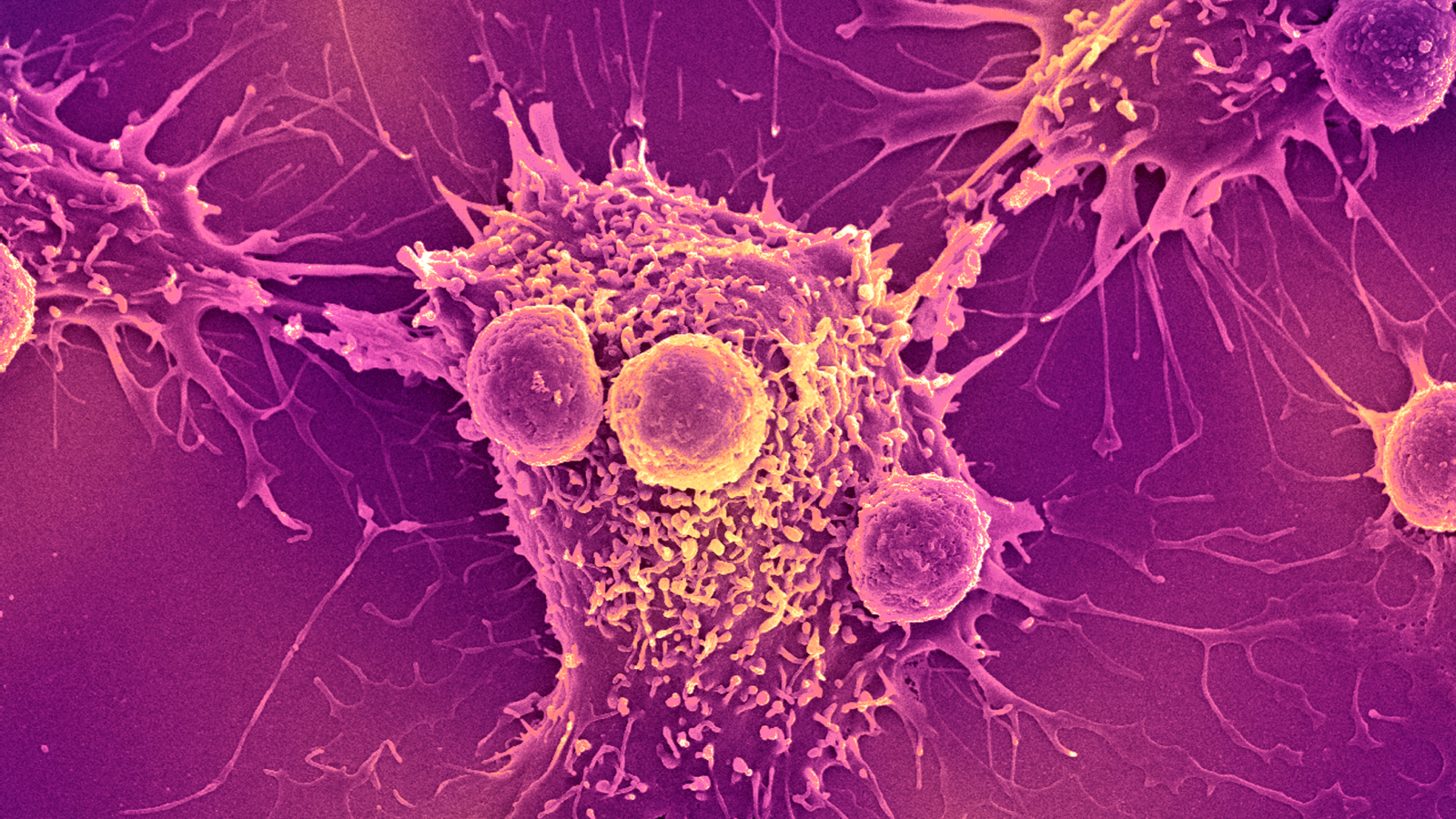

A new mRNA-based vaccine triggers a response from the innate immune system to help arm the body against cancer, a mouse study finds. It's now in early human trials.

A universal cancer vaccine in development could help rev up the immune system against tumors and supercharge the effects of existing cancer therapies, an animal study suggests.

Similar to vaccines for viral infections like the flu, many cancer vaccines are designed to help the immune system recognize specific proteins. However, while conventional vaccines aim to prevent disease, cancer vaccines are currently being developed to clear away cancers already growing in the body and to help prevent treated cancers from coming back.

Nonetheless, conventional vaccines and cancer vaccines often work similarly. The flu shot trains the immune system to look for unique proteins found on the surface of influenza viruses, while cancer vaccines typically teach immune cells to spot unique features of cancer cells.

But there's a challenge: These cancer proteins of interest can often be unique to individual patients, meaning each cancer vaccine may need to be specially formulated for each patient. Although it's possible to craft such personalized vaccines, they take time to make — and, in the interim, the patient's cancer mutates, potentially causing the vaccine to be less effective.