Gut microbiome strain-sharing within isolated village social networks

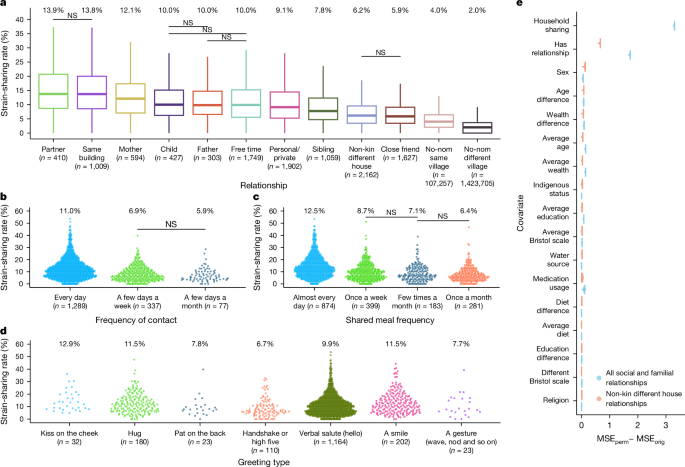

When humans assemble into face-to-face social networks, they create an extended social environment that permits exposure to the microbiome of others, thereby shaping the composition and diversity of the microbiome at individual and population levels1,2,3,4,5,6. Here we use comprehensive social network mapping and detailed microbiome sequencing data in 1,787 adults within 18 isolated villages in Honduras7 to investigate the relationship between network structure and gut microbiome composition. Using both species-level and strain-level data, we show that microbial sharing occurs between many relationship types, notably including non-familial and non-household connections. Furthermore, strain-sharing extends to second-degree social connections, suggesting the relevance of a person’s broader network. We also observe that socially central people are more microbially similar to the overall village than socially peripheral people. Among 301 people whose microbiome was re-measured 2 years later, we observe greater convergence in strain-sharing in connected versus otherwise similar unconnected co-villagers. Clusters of species and strains occur within clusters of people in village social networks, meaning that social networks provide the social niches within which microbiome biology and phenotypic impact are manifested.

The microbiome is known to play a role in many human phenotypes8. In turn, diet, medications, lifestyle and environmental exposures affect microbiome composition5,9,10. As few bacterial components of the microbiome survive for very long outside the human body, most must somehow be acquired from other humans through physical contact. Although maternal transmission is one obvious pathway6,11,12, adults may acquire microbial species from other people beyond their mothers via social interactions1. Indeed, in models involving both mice and primates, gut microbiome information can predict a host’s social interactions2,13,14,15,16,17,18. In humans, recent evidence indicates the salience of household and spousal transmission1,3,4. Yet, a substantially broader set of social relationships that people have—including in particular to unrelated people residing outside a person’s household—and the details of those social interactions (for example, their duration or frequency), are also likely relevant to a person’s microbiome composition.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/LUKPFIH5S5JKBMJFDLHCRXEDRE.jpg)