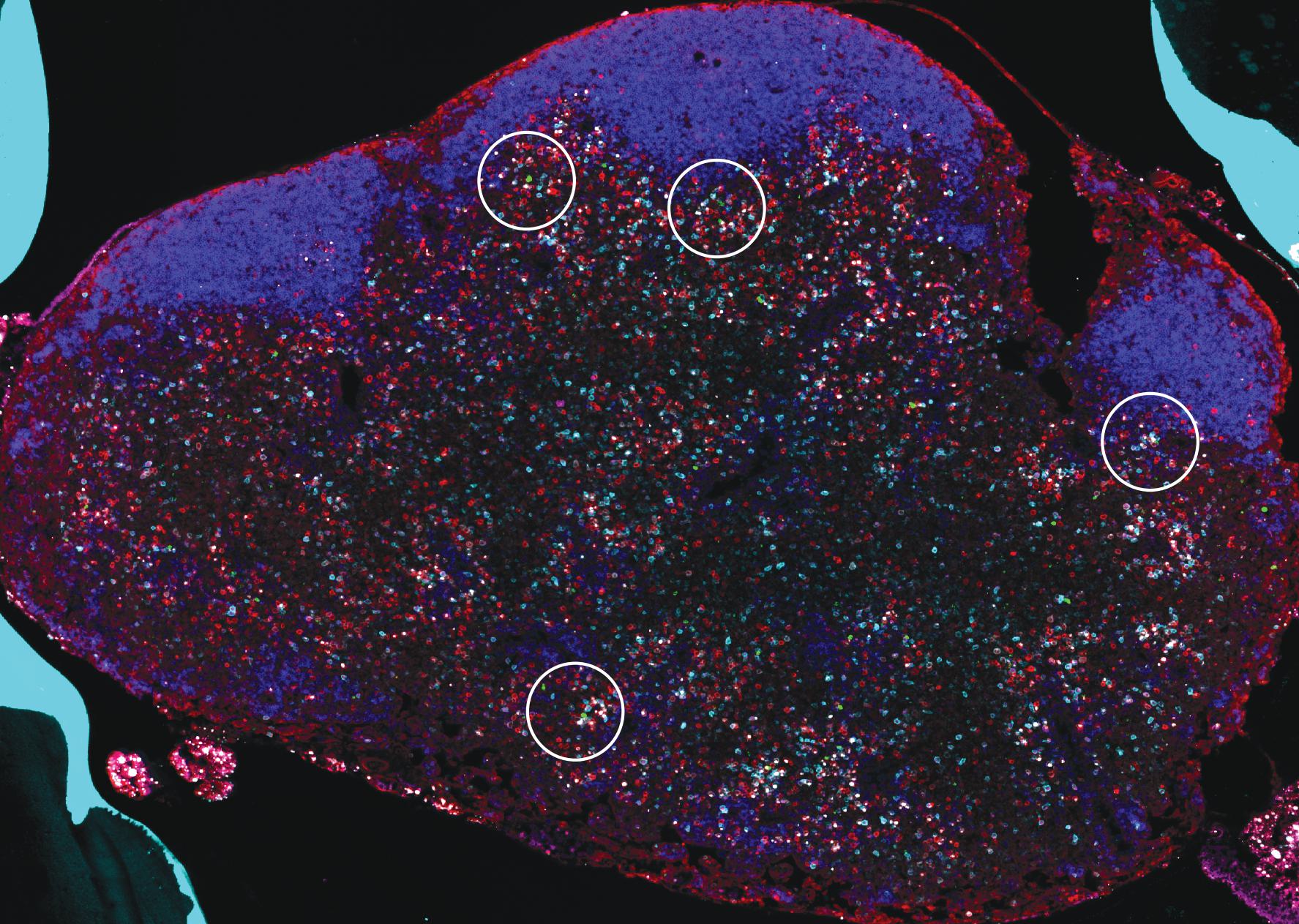

A Winning Photograph of Octopus Embryos with Chromatophores

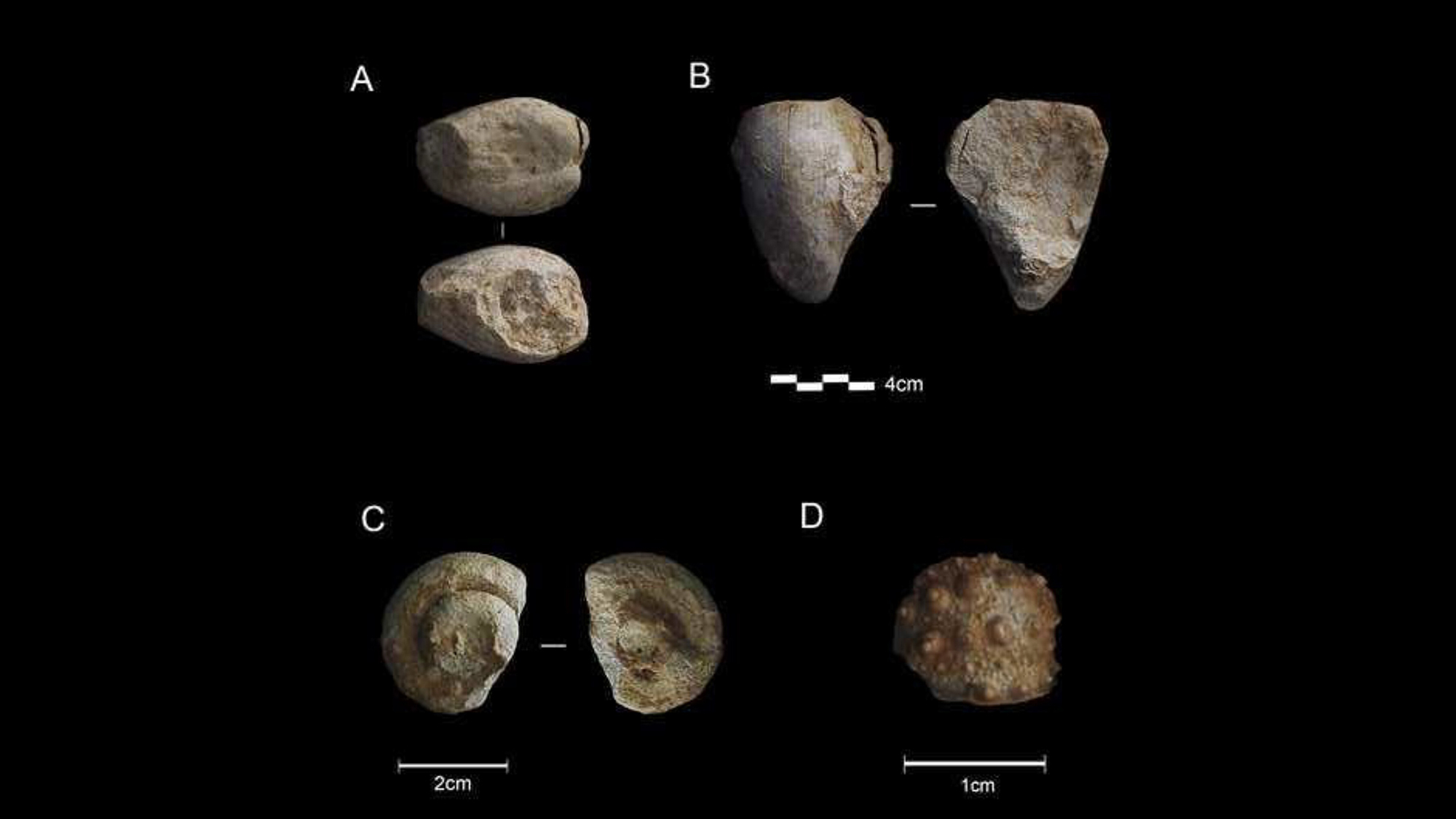

L ike tiny grapes tethered together by a vine, a clump of Caribbean two-spot octopus eggs (Octopus hummelincki) huddles under the watchful gaze of a magnified camera lens. The cluster, which measures just under 1 centimeter in diameter, holds the lives of dozens of fragile, weeks-old embryos.

The Caribbean two-spot octopus tends to shelter in the shallow costal shelves of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Very little is known about the species’ reproduction and development, but like most octopus species, it lays clusters of eggs that are knotted together by translucent strings and guarded in their nests. Mother octopods generally tend to and clean their offspring for weeks at a time—a period dependent upon the species and the surrounding water temperature—until the eggs hatch and start their life cycles as miniscule, planktonic larvae.

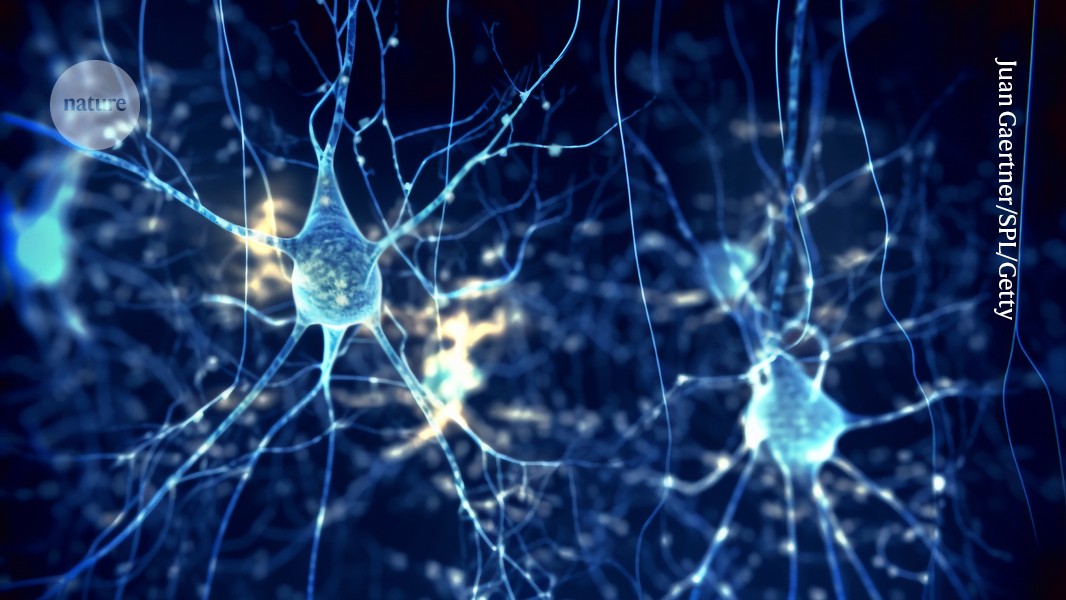

Like many other cephalopods, two-spot octopuses are masters of disguise. Observations from almost a century ago detail this octopus’ effective camouflaging practice, with one 1937 observation remarking on a wild two-spot octopus’ ability to rapidly alternate between mottled patterns and solid colors. Their colorful “flashing” is enabled by a complex web of chromatophores: These color-changing organs have a distinct pigment sac that sits beneath the surface of their skin and expands and contracts to reveal different hues.