Neanderthals may have enjoyed collecting tchotchkes—just like us

Humans love to collect things, even though it doesn’t always make sense from an evolutionary standpoint. From stamps, to comic books, to rare coins—if society attaches an emotional or economic value to items, then chances are some people will gather them. Collecting trinkets may not physically sustain you, but the act does indicate a certain level of cognitive capability and abstract thinking. But when did we first begin gathering objects just because we enjoyed them? Judging from relics uncovered in a cave in Iberia, Spain, the act of collecting may stretch at least as far back as our Neanderthal ancestry.

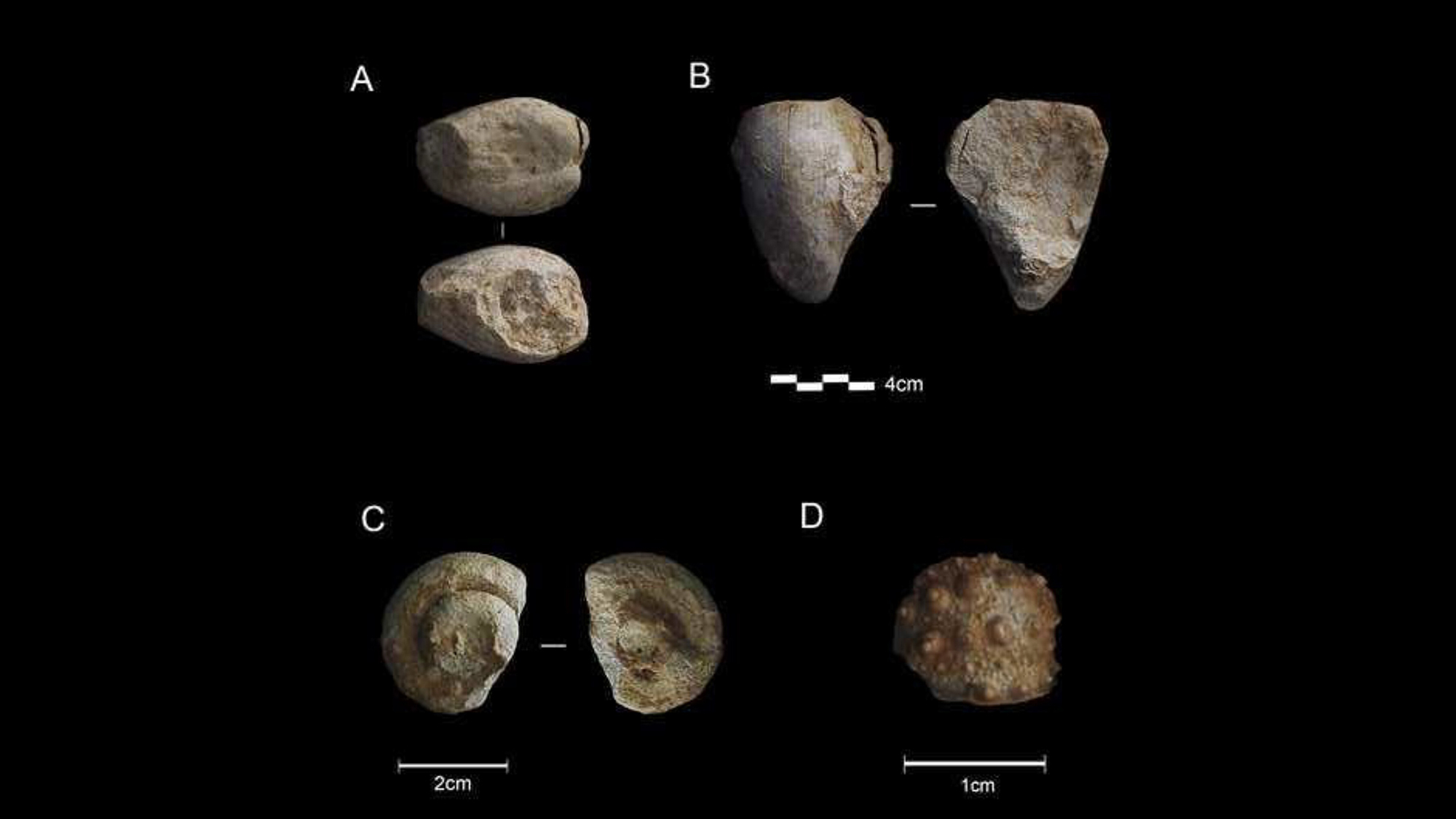

In a study published on November 12th in the journal Quaternary, an archeological team led by researchers at the Universidad de Burgos analyzed 15 small marine fossils found in the fourth level of the Prado Vargas Cave system in Burgos, Spain. While one artifact showed physical evidence of use as a hammer, the other 14 fossils displayed no obvious physical wear or utilitarian value. Additional evidence in the caves also points to the site serving as a semi-permanent Neanderthal encampment likely used for toolmaking, hunting, or perhaps even ritualistic activities. These shell fossils, which averaged under two inches in width, were dated to approximately 39.8–54.6 thousand years ago during the Upper Cretaceous Era, and included remains of species such as early sea snails and saltwater clams. But, as researchers note, none of them are native to the cave’s immediate region. Instead, the team estimates that many of the fossils’ nearest possible original location were in geological formations over 18.5 miles away.

Previous research shows Neanderthals engaged in cultural rituals such as ornamental crafting, cave wall art, and even familial and social funeral burials. Because of this, the experts argue that it stands to reason the human ancestors likely participated in pastimes such as collecting items they thought interesting or special.