At Mexico’s school for jaguars, big cats learn skills to return to the wild

In the grasslands of Yagul, in the central valleys of southern Mexico’s Oaxaca state, a jaguar makes its way through the bushes. It stops suddenly, lowering its head and sharpening its gaze, stalking. With its eyes on its target, it stealthily pounces on it. Just a short run and a jump before the jaguar’s prey is in its jaws.

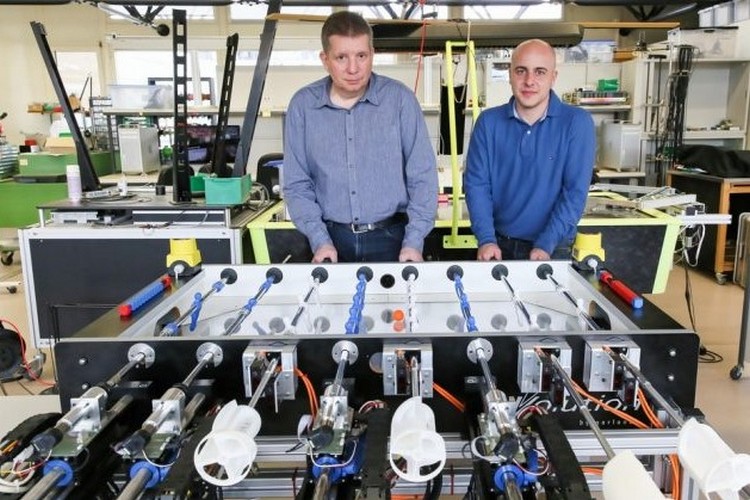

It sounds like a hunting scene from the wild, but this one is an exercise planned by a team of biologists, veterinarians and ethnologists. The prey isn’t a live animal, but a jute sack stuffed with chicken meat, strung from the end of a pole.

The exercise is meant to encourage the jaguar to relearn behavior from its former life in the wild: using its sense of smell to locate its target, its claws and muscles to climb the pole, and its bite and weight to break the rope that ties the chicken-stuffed bag together. Only in this way can it access its prize.

“This type of exercise keeps the jaguars active and reduces the impact of captivity and a sedentary lifestyle, which can cause stress and obesity,” says Víctor Rosas Cosío, a jaguar expert and project director of the Yaguar Xoo sanctuary, located 35 kilometers (22 miles) from the city of Oaxaca, the state capital.