Does Morality Do Us Any Good?

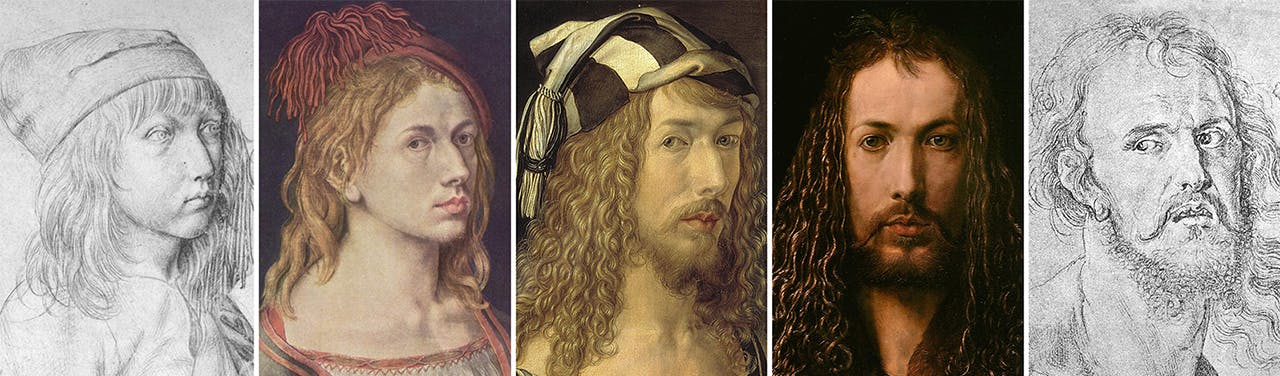

Nothing kills your appetite, they say, like discovering how the sausage is made. In the realm of superhero cinema, origin stories explain our protagonist’s driving motivations. But in the realm of faith and values? I stopped believing everything the tabloids said after I went on a school trip to the offices of my local paper. Others have grown disillusioned once they scrutinized the early history of their religion as historians, not as adherents. It’s harder to keep believing some things once you find out why you believe them.

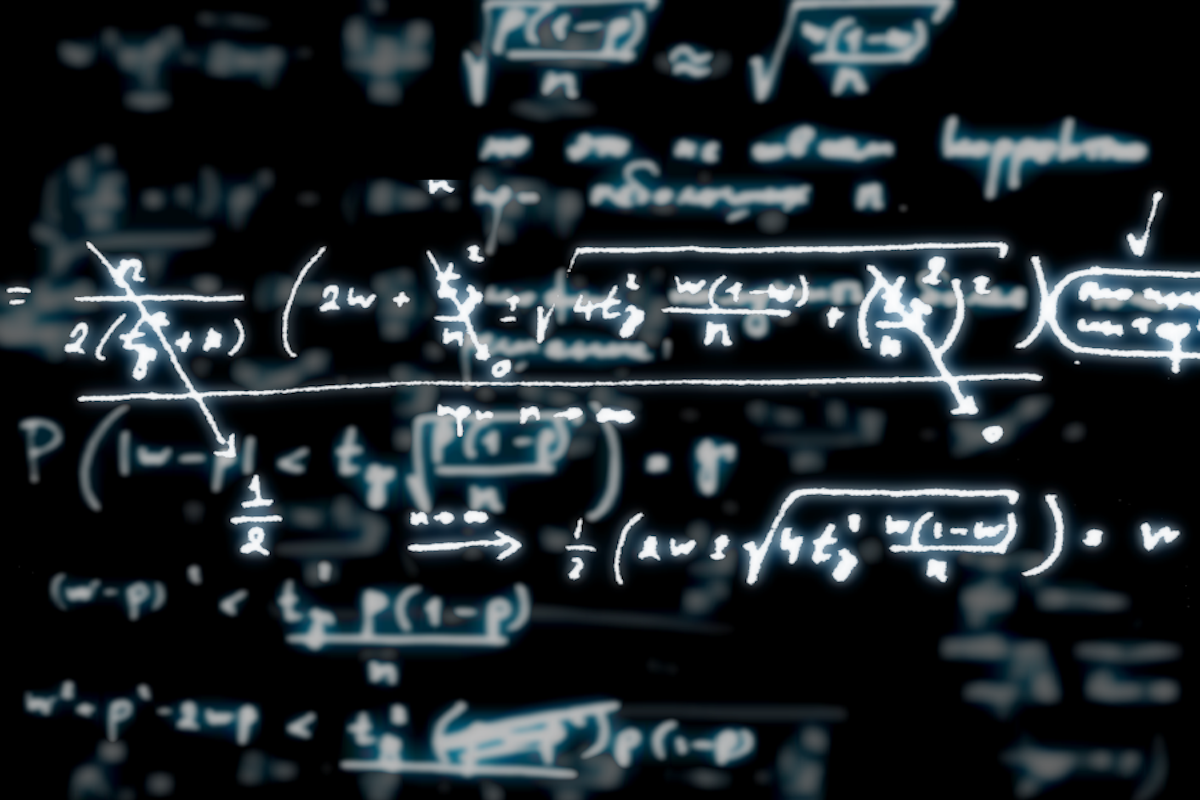

Naturally, I hold slavery to be an abomination and liberal democracies to be better than totalitarian dictatorships. But why? I could draw on my years of education to tell you it has something to do with my belief in freedom, autonomy, the awfulness of treating a fellow human being as a mere instrument. But a skeptic can point out that I had these convictions before I was ever in a position to articulate a cogent argument for them. The arguments came afterward; they are rationalizations of things I already believed.

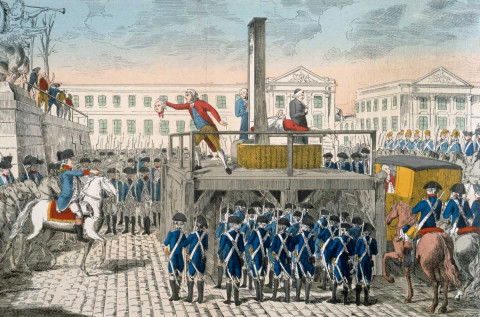

The unflattering truth, this skeptic might continue, is that my views on slavery simply reflect the moral common sense of the society I was born into. My affection for liberal democracy may come from the simple fact that I grew up in one, surrounded by its propaganda. Who knows what I’d think if I’d been raised as a member of a plantation-owning family in the antebellum South, where abolitionists were regarded as dangerous eccentrics? I used to fancy myself a rational creature who believed things for reasons; now, attuned to the question of origins, I see myself as no freer of the nexus of causes than my dog, my cactus, or my tennis ball.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16294981/akrales_190522_3440_0067.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25799983/247348_Nintendo_targeting_Youtuber_CVirginia_A.jpg)