/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25705153/247352_Election_Machine_AParkin.jpg)

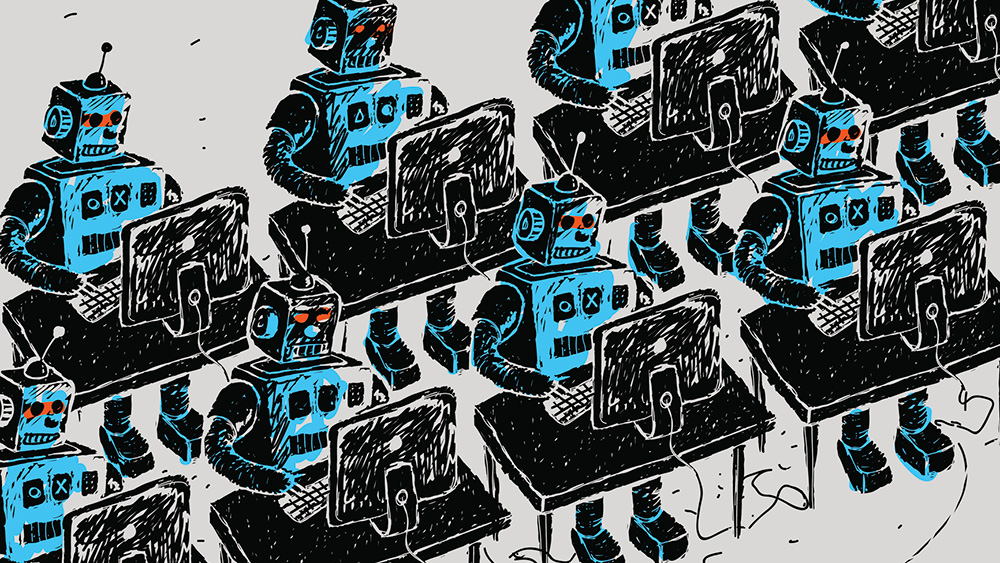

Voting machine companies are fighting the next disinformation war

By Lauren Feiner , a senior policy reporter at The Verge, covering the intersection of Silicon Valley and Capitol Hill. She spent 5 years covering tech policy at CNBC, writing about antitrust, privacy, and content moderation reform.

Ed Smith still remembers the weeks after Election Day 2020. The elections compliance expert worked for voting technology provider Smartmatic at the time: a mostly low-profile company that had supplied ballot-marking devices to Los Angeles County. As the polls reported their vote counts, though, then-President Donald Trump lost to challenger Joe Biden — and Trump launched an all-out war on the results. Companies like Smartmatic found themselves under siege.

Trump and his allies accused Smartmatic and its competitor Dominion Voting Systems of a conspiracy to rig the vote for Biden. And as Trump’s attorneys, Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani, piled up false claims in court, armies of online supporters descended on employees like Smith. Twitter users found his work history at several voting tech companies and concluded, “This must be the guy,” he recalls. People were “threatening me, wanting to come to my house and show me some love.” Smith had been proud of his years of experience — work he considered a public benefit. But as Trump undercut trust in the system, Smith’s own mother believed the election had been stolen. The misinformation and online attacks “just created a climate that led me to be very sad.”

Four years later, Trump is again on the ballot. He’s preemptively claimed his rivals want to steal the election and refused to guarantee he’ll accept the results. Dominion, Smartmatic, and other election tech providers are going on the offensive, trying to convince the public of their trustworthiness. But they’re contending with a problem that seems sometimes insurmountable: fighting conspiracy theories amid a crisis of trust.