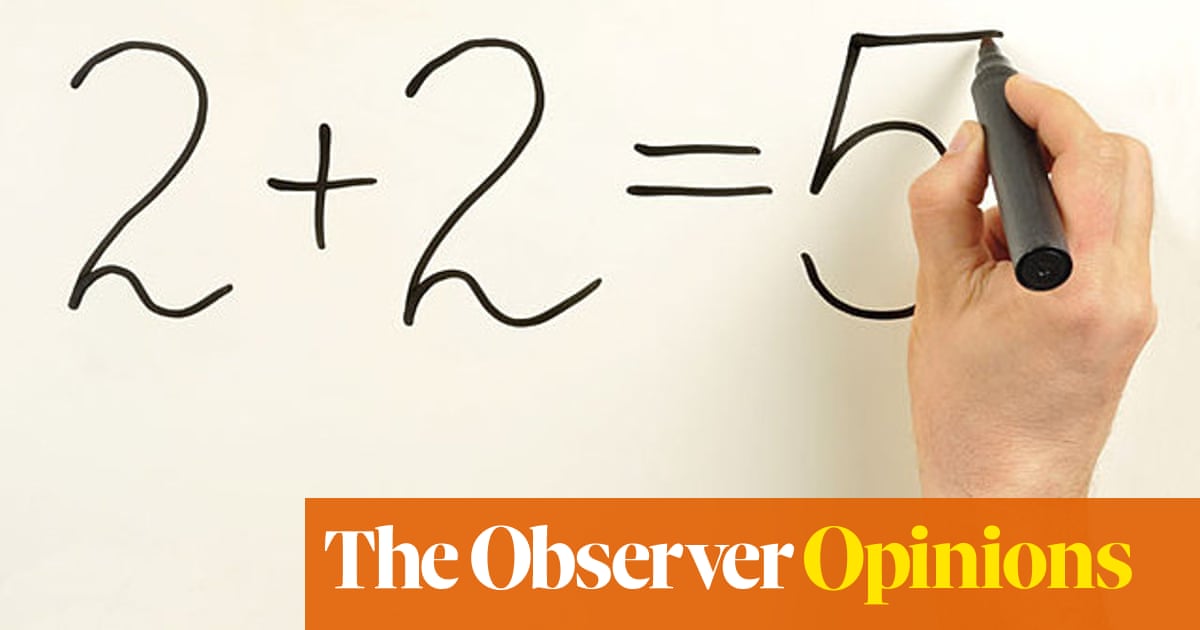

The dying art of the hatchet job

A few weeks ago, the New Statesman writer Sarah Manavis steeled herself for a backlash. “It’s always fun to post an article that you know beforehand will get very badly ratioed,” she tweeted after linking to a piece in which she called Apple TV+’s feelgood soccer sitcom Ted Lasso “the most overrated show on TV”. And so it came to pass. Three weeks later, she tweeted: “Despite spending most of my career writing about online radicalisation and disinformation, I’ve never received more abuse than when I criticised T*d L*sso.”

This is far from uncommon, for it’s increasingly common for critics to adopt the brace position before daring to dislike something that many people enjoy. Back in May, the Guardian’s Scott Tobias became Twitter’s baddie of the day for battering Shrek on the occasion of its 20thanniversary: “Shrek is a terrible movie. It’s not funny. It looks awful.” I found the reaction extraordinary. Tobias was called, at best, a cynical, click-hungry contrarian; at worst a twisted, misanthropic snob. “Shrek Fans Diss ‘Joyless Chud’ Guardian Critic Who Called Film ‘Unfunny and Overrated,’” reported The Wrap. His crime, let’s say it again, was hating an old, animated movie about an implausibly Scottish ogre and his donkey friend.

Critics have never been the world’s most beloved people. Almost exactly 100 years ago, the Czech author and sometime critic Karel Čapek wrote about the consequences of a harsh review: “I’m reconciled in advance to the fact that [the author] considers me unfair, cliquey and incompetent. It’s definitely his right. I, too, use this right when an unfair, cliquey and incompetent critic, who gives my book a bad press, hurts me. To cut a long story short, there’s an eternal conflict between artist and critic. ‘Praise me, or I’ll hate you.’”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24801728/Screenshot_2023_07_21_at_1.45.12_PM.jpeg)