Changes in Parents’ Mental Health Did Not Drive the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis

We love it when critics of our work propose alternative explanations for the youth mental health crisis. Zach and I keep a whole collaborative review doc full of such theories, which we invite you to view and comment on.

One alternative that some critics have recently proposed is that we shouldn’t be looking to the kids to find the source of the mental health crisis; instead, we should be looking to the parents. These critics argue that because parent-aged adults have higher rates of suicide than teens and those rates have been rising, it might be that parents got more depressed and suicidal in the 2010s, and that has—in turn—influenced their children.

Jean Twenge has been masterful at testing these alternative theories and showing that all of them contradict the timing, the demographics, or the international dimension of the epidemic. (See Jean’s post: Here are 13 Other Explanations for the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis. None of Them Work.) In fact, Jean’s latest post here at After Babel showed that Suicide Rates Are Now Higher Among Young Adults Than the Middle-Aged.

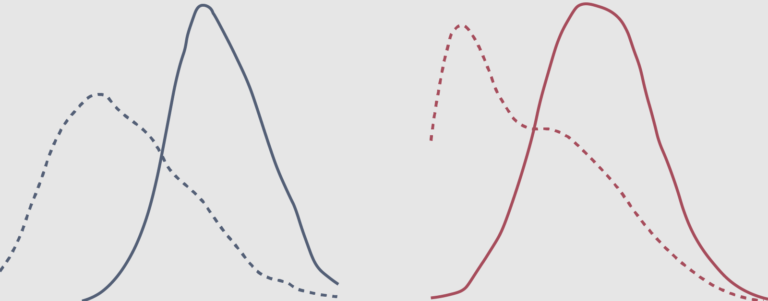

In today’s cross-post from her Substack, Generation Tech, Jean shows that the “parents first” hypothesis is out of sync with the cross-generational data from the 2010s. Jean’s post is important because—as far as we know—she is the first to use data that distinguishes between parents and non-parents. (This is not possible to do with suicide rate data). Her graphs below tell a powerful story: something happened to the teens, not to the parents, in the 2010s. She also shows that if anything happened to the adults, it seems to have mostly happened to the non-parents.