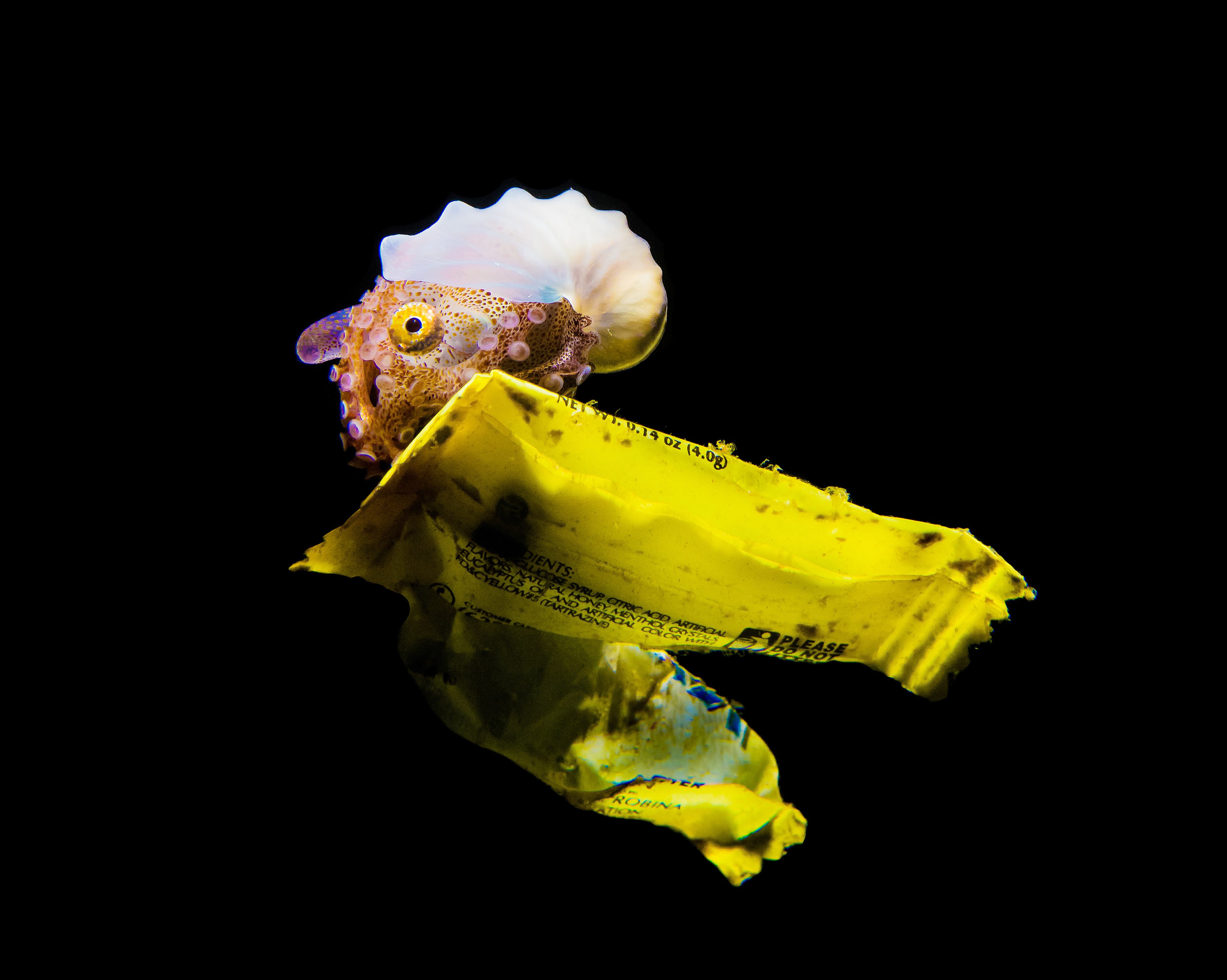

The Argonaut Octopus Has Mastered The Free Ride

In 2019, the photographer Harris Narainen had just wrapped up a night dive off Anilao in the Philippines and begun his staggered ascent to the surface when his dive leader pointed a flashlight at something bright and yellow. Narainen looked over and saw a tiny shelled octopus called an argonaut, or paper nautilus, clinging to the candy wrapper as if it were a magic carpet. "I was just too excited," Narainen wrote in an email. Earlier, the dive leader had mentioned they might see argonauts if they were lucky, and now here one was, sailing into the bright beam of light.

Although most octopuses live near the ocean floor and its ample hiding places, argonauts spend their entire lives sailing in the open ocean, just below the surface. This lifestyle has rendered the small cephalopods rather elusive to the scientists who wish to study them. "Most observations on argonauts are opportunistic," Roger Villanueva, a marine biologist at Spain's Institute of Marine Sciences (CSIC), wrote in an email. In many of these serendipitous observations, argonauts are spotted clinging to some kind of substrate, such as a twig of driftwood or some gelatinous creature. But a traditional sampling net cannot capture these associations; the turbulence of retrieval will separate an argonaut from its trusty steed or entangle it randomly with another.

Fortunately, argonauts are coveted subjects for many blackwater photographers, who dive at night with lights. Many of the creatures drawn to these lights are still in their larval stages, mostly translucent and often bearing little resemblance to their future selves. Villanueva, who has studied cephalopods for over 30 years, is particularly interested in the mystery of their early developmental stages, which "are traditionally poorly sampled and poorly understood compared to adults and offer many unanswered questions," he said.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19704536/acastro_200207_3900_firefox_0001.0.jpg)