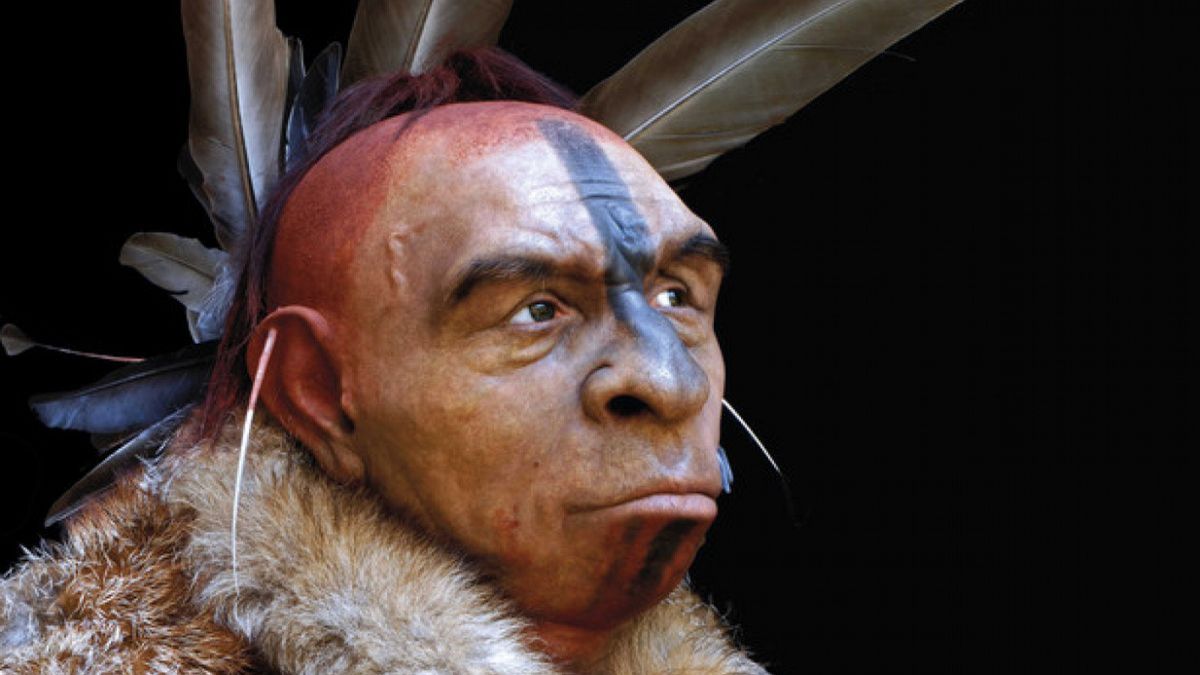

Did we kill the Neanderthals? New research may finally answer an age-old question.

About 37,000 years ago, Neanderthals clustered in small groups in what is now southern Spain. Their lives may have been transformed by the eruption of the Phlegraean Fields in Italy a few thousand years earlier, when the caldera's massive explosion disrupted food chains across the Mediterranean region.

They may have gone about their daily life: Crafting stone tools, eating birds and mushrooms, engraving symbols on rocks, and creating jewelry out of feathers and shells.

But the story of their extinction actually begins tens of thousands of years earlier, when the Neanderthals became isolated and dispersed, eventually ending nearly half a million years of successful existence in some of the most forbidding regions of Eurasia.

By 34,000 years ago, our closest relatives had effectively gone extinct. But because modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped in time and space for thousands of years, archaeologists have long wondered whether our species wiped out our closest relatives. This may have occurred directly, such as through violence and warfare, or indirectly, through disease or competition for resources.

Now, researchers are solving the mystery of how the Neanderthals died out — and what role our species played in their demise.