The Campus Does Not Exist

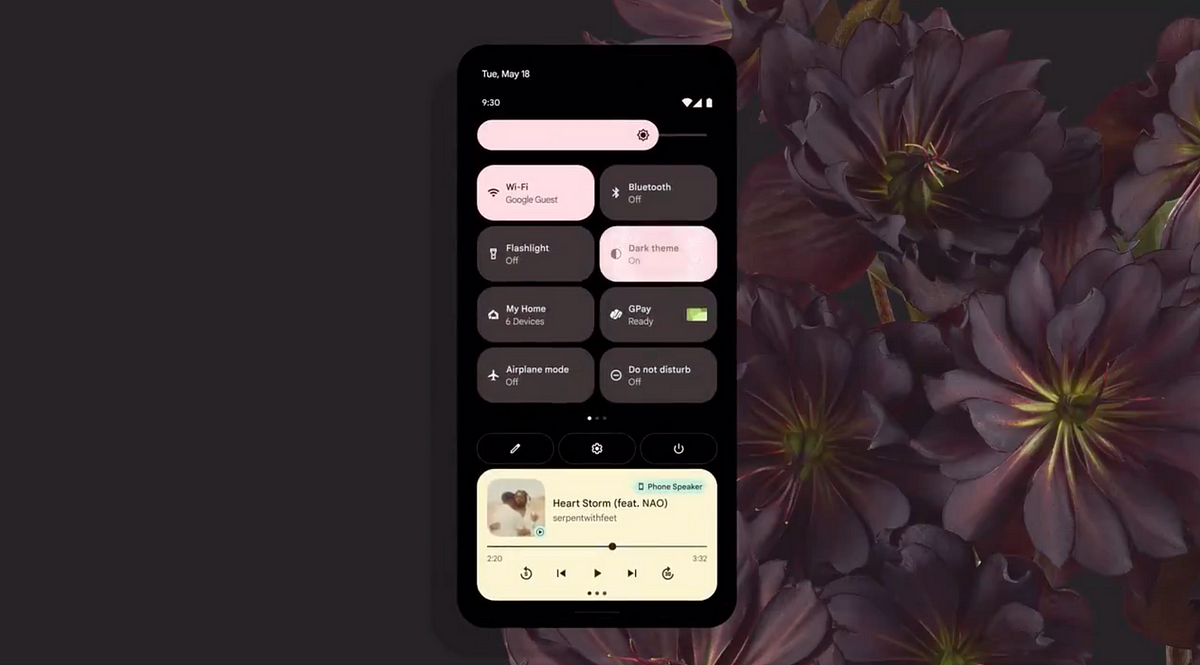

Recently, something did not happen to me. I am employed as a non-tenure-track professor in a university department dedicated to teaching and research about Jews, Judaism, and Jewishness. One day, I arrived at work to find security cameras installed in my department’s hallway. I read in an email that these cameras had been installed after an antisemitic poster was discovered affixed to a colleague’s office door. I was never shown this poster. Like the cameras, I learned of it only belatedly. Despite the fact that the poster apparently constituted so great a danger to the members of my department as to warrant increased security, nobody bothered to inform me about it. By the time I was aware that there was a threat in which I was ostensibly implicated, the decision had already been made—by whom, exactly, I don’t know—about which measures were necessary to protect me from it. My knowledge, consent, and perspective were irrelevant to the process, in which I was not an agent but an object: an asset to be safeguarded; a liability to be managed; an investigation to be foreclosed. The prolepsis of the decision did more than protect me—if, indeed, it really did that. It interpellated my coworkers and myself as people in need of protection. I was not a victim, yet the very presence of this camera figured me as somebody who might imminently become one. I wasn’t afraid, but the camera figured me as somebody who ought to be. It figured me, in short, as a target. Precisely because something had not happened to me, I was unwittingly transformed, literally overnight, into the type of person to whom something might happen. My employer has a campus—three, actually—meaning that it has a physical plant. I navigate one of these campuses as my workplace, but it almost never figures for me as “the campus.” In fact, the first time since beginning the job when I felt myself caught up in an affective relation, not to the particular institution where I work, but rather to “the campus” was when I looked up into that security camera and felt myself being “watched” by it. Only then did I think, a couple of months into my temporary contract, that I was not just at my workplace. Now I was on “the campus.” This incident with the poster and the camera occurred, of course, some weeks after the October 7 Hamas attacks on Israel and the onset of Israel’s retaliatory military campaign in Gaza. Against so horrific a backdrop, and relative to the intimidation and retaliation to which those who speak out against the war (including—indeed, especially—in the academy) have been subjected, my story sounds banal. And it is. In its very ordinariness, however, the anecdote is quite representative: first, of how decisions get made at contemporary institutions of higher education (generally speaking, without the input of those whom they impact); and second, of the logic of a peculiarly American phenomenon I call campus panic.

The months since October 7 have aggravated the most extreme campus panic I have witnessed. To judge by the American mass media, the campus is the most urgent scene of political struggle in the world. What is happening “on campus” often seems of greater concern than what is happening in Gaza, where every single university campus has been razed by the IDF. When all the Palestinian dead have been counted, it seems likely that these months will be recorded as having inflamed a campus panic no less intense than the one that accompanied the Vietnam War. The correspondences between that moment and this one were unmistakable to those of us who watched, in person or through screens, as the NYPD hauled 108 Columbia University students off of their institution’s campus on Thursday, April 18, 2024. Like the campus panic of the 1960s–70s, this one is aroused by the spectacle of young people speaking out against the inhumane actions of the US and its imperial client states, as well as against the complacency and complicity of their own educational institutions. Now, as then, the act of protesting against injustice undergoes a curious transfiguration in the media, which refashions this action into the object of frantic scrutiny, surveillance, and suppression. Harvard University professor Walter Johnson, in an essay about experience of working at Harvard since October 7 titled “Living Inside a Psyop”—the psyop being, precisely, “the campus”—calls this the “two-step maneuver” of campus panic: (1) Look over here, (2) Do not look over there. Overreact to this, overlook that.[1] Look at the US, not at Palestine. Look up at what is happening in the clouds over Cambridge, Massachusetts, where a plane trails a banner declaring, “HARVARD HATES JEWS”; do not look at what is happening on the ground in Gaza, do not look at the masses of the displaced, the bereaved, the starving, the wounded, the sick, the dying, and certainly do not look at the dead, murdered with artillery supplied by the US government and funded by American citizens’ taxes. When student protestors chant, “From the river to the sea,” hear a speculative antisemitic canard; do not hear a reference to an actual river, an actual sea, an actual and ongoing history of dispossession and occupation. Of course, one objective of such a protest is often to direct public attention in exactly the opposite direction. A protest demands that we look toward it, but only so that it can reroute our gaze to the thing being protested. The two-step hypostatizes the dynamic speech act of protest, dissevering it from its referential function so that it cannot achieve its goal. The cameras of the mass media turn away from the referent and toward the protest, which is presented to the audience as the actual crisis worthy of our attention, fury, and terror. In the present instance, glossing the protest as antisemitic occludes its intended referent from public view. It is easy enough to see how such a maneuver furthers the propaganda aims of both the American and the Israeli governments. What is less obvious, though, is why the camera turns toward the campus in particular. The American media’s obsession with—its panic about—the campus has pervaded coverage of the war, to the point that this coverage ceases, really, to be coverage of the war at all. To some extent it is a matter of supply generating demand. The US is, after all, a nation whose local newspapers consist mainly of syndicates of a very few for-profit conglomerates, while social media platforms subject users to the (again profit-motivated) whims of an algorithmic apparatus which is, at best, only glancingly and accidentally concerned with the tedious business of actually informing people. That narratives about “campus antisemitism,” “the campus free speech debate,” and “campus culture wars” are manufactured to appeal to consumers and thereby drive revenue, however, still does not explain why the narrative is appealing. Harvard, for instance, educates about 0.047% of the total current American undergraduate population. Yet, somehow, the assertion that this institution “hates Jews” occupies a more prominent place in public discourse than the fact that a considerably greater percentage of the total Palestinian undergraduate population has been bombed out of existence or turned refugee. The war on Gaza is being rewritten for American audiences as a “campus war.” Often quite literally: for example, in March 2024 the Atlantic, a sort of conservatism-laundering machine for liberal elites, ran an essay by a Stanford University sophomore under the title, “The War at Stanford.”[2]