Rule of the Pharaohs

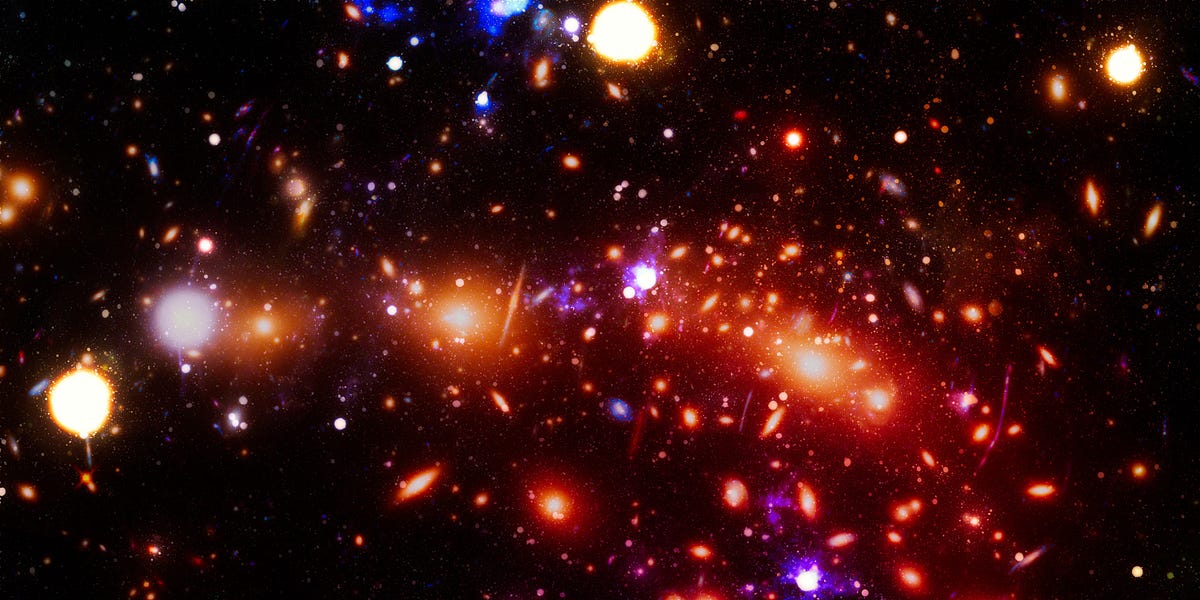

Twenty miles south of Cairo, on the Nile's west bank, where riverfed crop fields give way to desert, the ancient site of Saqqara is marked by crumbling pyramids that emerge from the sand like dragon's teeth. Most striking is the famous Step Pyramid, built in the 27th century B.C. by Djoser, the Old Kingdom pharaoh who launched the tradition of constructing pyramids as monumental royal tombs. More than a dozen other pyramids are scattered along the five-mile strip of land, which is also dotted with the remains of temples, tombs and walkways that, together, span the entire history of ancient Egypt. But beneath the ground is far more—a vast and extraordinary netherworld of treasures.

One scorching day last fall, Mohammad Youssef, an archaeologist, clung to a rope inside a shaft that had been closed for more than 2,000 years. At the bottom, he shined his flashlight through a gap in the limestone wall and was greeted by a god’s gleaming eyes: a small, painted statue of the composite funerary deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, with a golden face and plumed crown. It was Youssef’s first glimpse of a large chamber that was guarded by a heap of figurines, carved wooden chests and piles of blackened linen. Inside, Youssef and his colleagues found signs that the people buried here had wealth and privilege: gilded masks, a finely carved falcon and a painted scarab beetle rolling the sun across the sky. Yet this was no luxurious family tomb, as might have been expected. Instead, the archaeologists were astonished to discover dozens of expensive coffins jammed together, piled to the ceiling as if in a warehouse. Beautifully painted, human-shaped boxes were stacked roughly on top of heavy limestone sarcophagi. Gilded coffins were packed into niches around the walls. The floor itself was covered in rags and bones.

This eerie chamber is one of several “megatombs,” as the archaeologists describe them, discovered last year at Saqqara, the sprawling necropolis that once served the nearby Egyptian capital of Memphis. The excavators overseen by Youssef uncovered hundreds of coffins, mummies and grave goods, including carved statues and mummified cats, packed into several shafts, all untouched since antiquity. The trove includes many individual works of art, from the gilded portrait mask of a sixth- or seventh-century B.C. noblewoman to a bronze figure of the god Nefertem inlaid with precious gems. The scale of discoveries—captured in the Smithsonian Channel documentary series “Tomb Hunters,” an advance copy of which was made available to me—has excited archaeologists. They say it opens a window into a period late in ancient Egyptian history when Saqqara was at the center of a national revival in pharaonic culture and attracted visitors from across the known world. The site is full of contradictions, entwining past and future, spirituality and economics. It was a hive of ritual and magic that arguably couldn’t seem more distant from our modern world. Yet it nurtured ideas so powerful they still shape our lives today.