The Magic Mountain Saved My Life

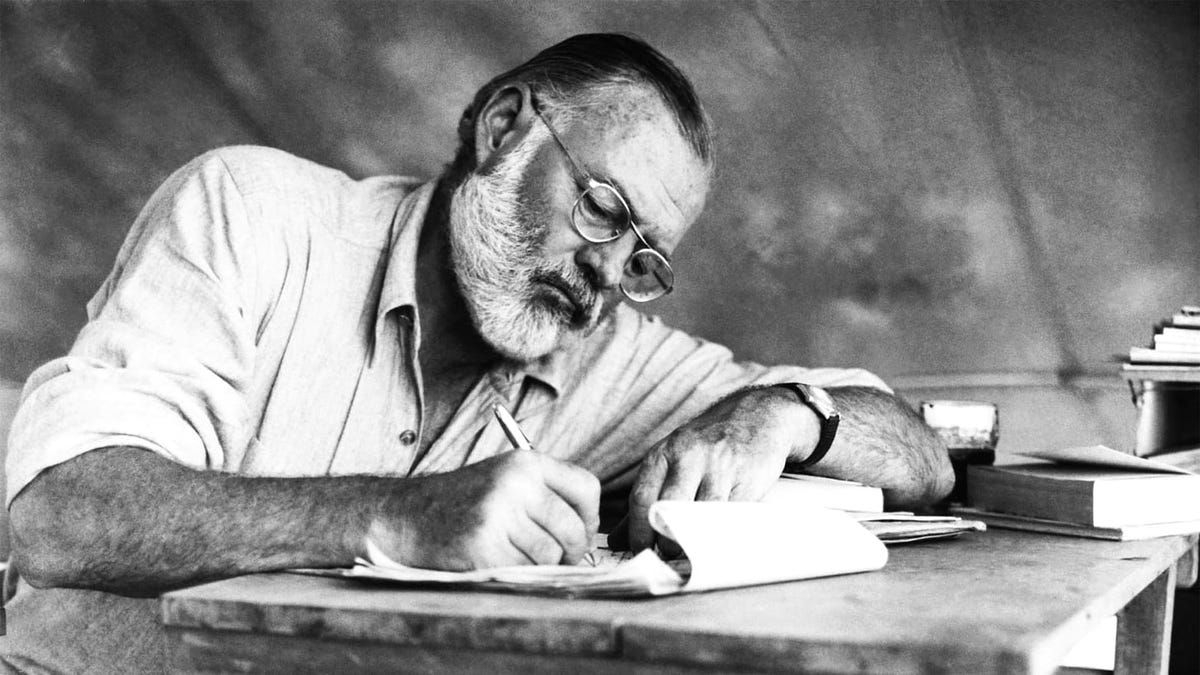

Just after college , I went to teach English as a Peace Corps volunteer in a small village school in West Africa. To help relieve the loneliness, I packed a shortwave radio, a Sony Walkman, and, among other books, a paperback copy of Thomas Mann’s very long novel The Magic Mountain. As soon as I set foot in Togo, something began to change. My pulse kept racing; my mouth went dry and prickly; dizzy spells came on. I developed a dread of the hot silence of the midday hours, and an awareness of each moment of time as a vehicle for mental pain. It might have helped if I’d known that my weekly antimalarial medicine could have disturbing effects, especially on dreams (mine were frighteningly vivid), or if someone had mentioned the words anxiety and depression to me. At 22, I was a psychological innocent. Without the comfort of a diagnosis, I experienced these changes as a terrifying void of meaning in the universe. I had never noticed the void before, because I had never been moved to ask the questions Who am I? What is life for? Now I couldn’t seem to escape them, and I received no answers from an empty sky.

I might have lost my mind if not for The Magic Mountain. By luck or fate, the novel—which was published 100 years ago, in November 1924—seemed to tell a story a little like mine, set not in the West African rainforest but in the Swiss Alps. Hans Castorp, a 23-year-old German engineer, leaves the “flatlands” for a three-week visit to his cousin Joachim, a tuberculosis patient who is taking the cure in one of the high-altitude sanatoriums that flourished in Europe before the First World War. Hans Castorp (Mann’s detached and amused, yet sympathetic, narrator always refers to the protagonist by his full name) is “a perfectly ordinary, if engaging young man,” a slightly comical young bourgeois.